There are those of us who are familiar with the old motto “You have to go out, but you don’t have to come back.” It originated in the days of the old U.S. Life-Saving Service and continued to be quoted for a while in the modern Coast Guard.

The motto originated with the necessity, mandated by contemporary service regulations, for a lifesaving crew to attempt its rescue regardless of weather or sea conditions. Excuses, such as “It was too rough” or “The storm was too severe,” would not be accepted by the service. This requirement was in effect from the latter Life-Saving Service era (ca. 1900-1915) well into the 20th century.

The motto originated with the necessity, mandated by contemporary service regulations, for a lifesaving crew to attempt its rescue regardless of weather or sea conditions. Excuses, such as “It was too rough” or “The storm was too severe,” would not be accepted by the service. This requirement was in effect from the latter Life-Saving Service era (ca. 1900-1915) well into the 20th century.

But how did the old saying come about, and how was it actually codified into Life-Saving Service lore and tradition?

In the beginning of Life-Saving Service operations in the 1870s and 1880s, there existed no guidance for rescuers at the scene of a shipwreck. The guiding principle was to save lives first then save property. Published in 1873, the service’s first edition of its regulations as well as the second edition in 1884, make no mention of attempting a rescue using all available means. The June 1878 Congressional act that established the Life-Saving Service as an agency within the Treasury Department also made no mention of rescue requirements. However, it did note that cases involving loss of life required a formal investigation. This inquiry requirement determined if the loss of life was the result of poor judgment or incompetence by the responding station keeper and crew.

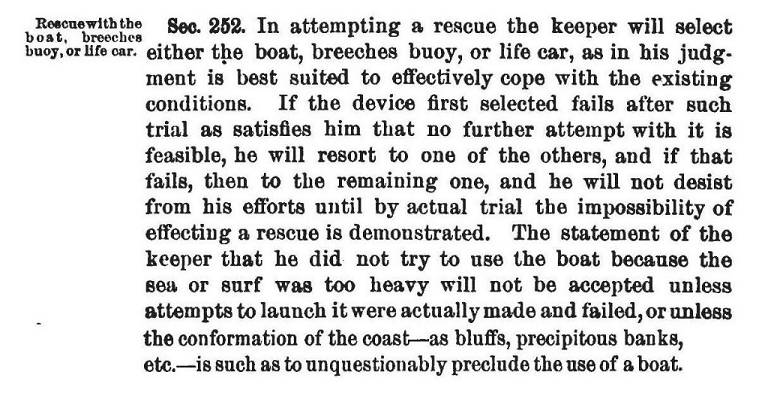

It was not until revised regulations were issued in 1899 that requirements were mandated regarding the actions taken by Life-Saving Service station crews. These requirements included attempting a rescue using every means possible at the crew’s disposal. These regulations continued in force beyond 1915, when the Life-Saving Service and U.S. Revenue Cutter Service merged to form the U.S. Coast Guard.

Bound in a royal blue cover, and referred to as the “Blue Book,” the 1916, 1917, 1921, 1922, and 1934 editions of the Coast Guard’s Instructions for Coast Guard Stations included the same regulation, derived word-for-word from the Life-Saving Service’s 1899 regulations, Article VI, Section 252. Even as late as the June 1949 edition of the Coast Guard’s Manual for Lifeboat Stations, CG-212, “Part C: Station Activities, Section C-1: General” mandated:

edition of the Coast Guard’s Manual for Lifeboat Stations, CG-212, “Part C: Station Activities, Section C-1: General” mandated:

Having departed for a scene of distress, a station boat or detail shall not turn back until a thorough search has been made and proved fruitless, or an order to return has been received from superior authority, or definite information has been received that no further assistance is needed, or in the judgement of the person in charge it becomes a physical impossibility to proceed.

Similarly, “Section C-2: Assistance,” mandated “In rendering assistance, the equipment best suited to cope with the type of disaster under prevailing conditions shall be selected. Should the equipment first selected prove inadequate, additional equipment shall be tried.” From a historical perspective, there was certainly a mandate in the regulations for the station crew to make the attempt using all available equipment at the station.

Separate from the written regulations are the words exchanged between a Life-Saving Service keeper and a surfman during an actual rescue. One of the more famous keepers on North Carolina’s Outer Banks was Patrick Etheridge, who was born in 1851 and died 1920. Etheridge started out as a surfman at Station Cape Hatteras, serving from 1882 to 1890 and, in 1891, was appointed to the position of the station’s keeper. In 1909, Keeper Etheridge was transferred to Station New Inlet, serving there from 1909 to 1914. In 1914, he was then transferred to Station Bodie Island where he served until March 26, 1915, when he retired after 33 years of service.

The famous statement attributed to Etheridge, and the circumstances under which it was said, go something like this: a surfman voiced his concern that, under the stormy conditions of heavy seas and surf, the crew might get through the surf to the shipwreck in the station’s surfboat, but might not make it back. In response, Etheridge shouted: “The Blue says we’ve got to go out and it doesn’t say a damn thing about having to come back!”

At one time, the rescue case in question was thought to be the December 1885 wreck of Barkentine Ephraim Williams—a rescue for which Etheridge and others were awarded the Gold Lifesaving Medal for heroism. The problem with this supposition is that the Life-Saving Service regulations (a.k.a., the “Blue Book”) in effect at the time was the 1884 edition, which made no mention of rescue crews attempting a rescue no matter what the circumstances.

More likely, the motto stemmed from a different rescue that occurred in late December 1904. In this case, the steamship Northeastern ran aground during a severe storm on North Carolina’s Diamond Shoals and started breaking up. In this storm, heavy wind and sea conditions were truly extreme. The station’s logbook relates a rescue in which the heavy breakers hurled the station surfboat onto the beach each time it was launched. It took a full day before the crew could get through the surf to the wreck and rescue survivors.

Although the logbook entries for the rescue make no mention of what was said by anyone, it does give a sense of how dangerous the mission was. That Etheridge said something to motivate his surfman to action is supported by a letter published on page two of the March 1954 edition of U.S. Coast Guard Magazine. Retired Chief Boatswains Mate Clarence Brady, who served with Etheridge while Etheridge was station keeper, wrote that Etheridge made the statement during the rescue attempt.

The matter becomes even more confused, however. A different claim is made in the Manteo, N.C., newspaper Dare County Times, in the June 12, 1946, edition. In an article by Thomas Barnett entitled “Hatteras Reminisces of the Days of Cap’n Pat,” the writer recounted the witness to a shipwreck, who shouted to Etheridge, “Why man, you will never get back, with a storm like this blowing you away from the beach.” To this, Etheridge allegedly replied, “The regulations do not say anything about coming back. They say, go.”

The matter becomes even more confused, however. A different claim is made in the Manteo, N.C., newspaper Dare County Times, in the June 12, 1946, edition. In an article by Thomas Barnett entitled “Hatteras Reminisces of the Days of Cap’n Pat,” the writer recounted the witness to a shipwreck, who shouted to Etheridge, “Why man, you will never get back, with a storm like this blowing you away from the beach.” To this, Etheridge allegedly replied, “The regulations do not say anything about coming back. They say, go.”

It is nearly certain that Keeper Etheridge said something to urge the crew to proceed with the rescue attempt. Based on surviving records, the exact wording of his admonition will probably never be known. It is also likely that the Life-Saving Service took whatever he actually said and transformed it into a service motto symbolic of the heroism that defined the service and its missions.

The old motto, however, was eventually tempered due to some tragic accidents with the loss of Coast Guard rescuer lives. It was changed in March 2018 to the current requirement described in the Coast Guard Commandant’s Instruction CI 3500.3A. This instruction requires rescuers to balance the immediate needs of a rescue case against the risk of personal injury to the rescue crew. This approach includes the implementation of the “Green/Amber/Red” (GAR) risk assessment system the Coast Guard uses today. These requirements are also described in instructions for Coast Guard boat coxswains and boat crew operations.

What is clear is that Keeper Patrick Etheridge and his crew successfully carried out the rescue of the Northeastern under extreme conditions of storm winds and heavy surf. They did so in an oar-powered, wooden surfboat, demonstrating the determination that all Life-Saving Service and Coast Guard crews have had and will continue to have in saving lives in peril on the sea.