EDITOR'S NOTE: This story first appeared in the Coast Guard Compass March 25, 2019.

In a service with limited resources to research its own history, many Coast Guard stories of the past remain untold or unknown. Additionally, the smaller communities outside of cutter and aviation forces get lost in the complex identity of a service made up of five other services and ever-changing missions.

The Coast Guard marked the 70th anniversary of the creation of the journalist rating in 2018, which was one of the two predecessor ratings of the current public affairs specialist rating. Public affairs specialists, in particular, remain an elusive and widely misunderstood part of the Coast Guard and the history of the rating is even more mysterious.

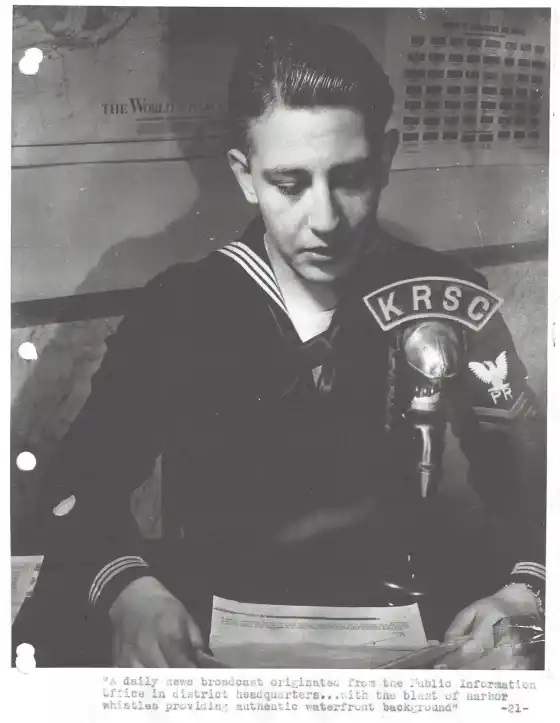

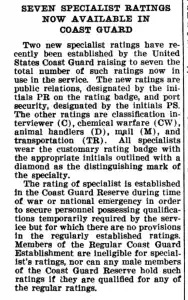

The Coast Guard laid the foundation for the journalist rating during World War II when the United States entered into an information war to counter enemy propaganda and to gain the support for the war from the American people. All of the military branches expanded their public affairs programs (still called public relations at the time) during our efforts in WWII. In the Coast Guard, this included the addition of a temporary enlisted rating for public relations in 1943.

Temporary, or “specialist,” ratings allow the service to add specific skills, mostly to the Coast Guard reserves, needed to complete missions during times of war. In WWII, the Coast Guard created as many as 10 specialist ratings, which included jobs such as dog-horse handler, classification interviewer, chemical warfare, teacher, and public relations. To control the expansion of new specialist ratings, the Coast Guard needed to justify more than 100 jobs, also known as billets, before creating a specialist rating. As the demand for a particular skill grew or diminished, the specialist ratings could be adjusted or abolished as need ed.

ed.

Specialists (public relations) worked at Coast Guard Headquarters, district public relations offices, and deployed overseas as combat correspondents. They commonly worked alongside photographer’s mates, the imagery side of public affairs. Without a formal training program, the Coast Guard recruited civilian public relations practitioners for the specialist jobs and relied on their industry expertise and newspaper contacts to publish stories about the service’s contributions to WWII.

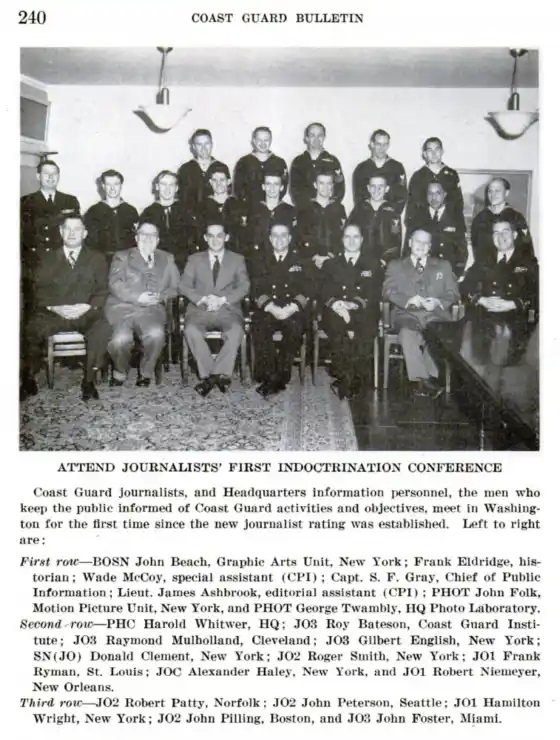

After the war, the Coast Guard eliminated m ost of the specialist ratings including public relations. Any correspondents who remained on active duty became a sub-specialty of the yeoman rating known as yeoman (PI). The service reorganized its entire enlisted structure by creating, eliminating and combining several enlisted ratings on April 2, 1948. As part of that initiative, the Coast Guard established and renamed the yeoman (PI) sub-specialty as its own rating, which would be known as journalists.

ost of the specialist ratings including public relations. Any correspondents who remained on active duty became a sub-specialty of the yeoman rating known as yeoman (PI). The service reorganized its entire enlisted structure by creating, eliminating and combining several enlisted ratings on April 2, 1948. As part of that initiative, the Coast Guard established and renamed the yeoman (PI) sub-specialty as its own rating, which would be known as journalists.

In the summer of 1949, Alex Haley, the most famous Coast Guard journalist to date, received a transfer into the rating and would become the first chief journalist of the Coast Guard in December later that year. Haley and his fellow journalists continued to support Coast Guard missions by writing articles and press releases to inform the public for the next two and a half decades.

In 1973, the Coast Guard combined the journalist and photographer’s mate ratings to form the photojournalist rating, which was renamed to public affairs specialist in 1984. Today, there are approximately 75 public affairs specialists on active duty who manage the Coast Guard’s day-to-day external communications and deploy to major incidents to conduct public information campaigns.