Clarence Lorenzo Samuels should be remembered as one of the most important minority trailblazers in the history of the U.S. military. Born and raised in Panama, Samuels enlisted at the age of 20 aboard the Cutter Earp when

Clarence Lorenzo Samuels should be remembered as one of the most important minority trailblazers in the history of the U.S. military. Born and raised in Panama, Samuels enlisted at the age of 20 aboard the Cutter Earp when it visited the Panama Canal Zone in 1920. At that time, the U.S. military categorized recruits by color alone and not ethnicity, so the service considered Samuels a “negro” rather than the Afro-Latino-American recruit that he was. During the course of his career, he would break many of the U.S. military’s color barriers for blacks and Hispanics.

it visited the Panama Canal Zone in 1920. At that time, the U.S. military categorized recruits by color alone and not ethnicity, so the service considered Samuels a “negro” rather than the Afro-Latino-American recruit that he was. During the course of his career, he would break many of the U.S. military’s color barriers for blacks and Hispanics.

An experienced mariner and natural leader, Samuels rose quickly through the enlisted ranks. He received the rank of seaman second class upon enlisting and, over the next eight years, he became a naturalized citizen and saw sea time aboard five different cutters. In July 1928, he received command of the 67-foot harbor patrol cutter Tybee (AB-15), home-ported in Savannah, Georgia. This would be a rapid rise for any enlisted man, but Samuels was a black man serving in Georgia in the 1920s. With racism and Jim Crow laws institutionalized in the South at that time, Samuels’ rise through the enlisted ranks proved very impressive.

Some historians have credited Samuels as the first minority man in uniform to take charge of a federal vessel due to his command of the Tybee. Revenue Cutter Service officer Michael “Hell Roarin’ Mike” Healy, the son of a slave and a plantation owner, commanded cutters decades before Samuels and could claim that title; however, Healy’s skin color appeared to be white and, in the highly racist American culture of the 19th-century, he refused to admit his racial background to others. On the other hand, others recognized Clarence Samuels as a man of color. To some, this qualified him as the first black federal ship commander and, given his Hispanic ethnicity, he qualifies as the service’s first Latino cutter commander.

In the years leading up to World War II, a time when black Coast Guardsmen served mainly in food service ratings, Samuels received a variety of non-food service enlisted assignments. In 1929, the Coast Guard advanced him to chief quartermaster. This was historic in many ways. To start, he was one of the first minority individuals to achieve what was then the highest enlisted rank in the service. In addition, he was the first minority service member to serve in the quartermaster rating, one of the most responsible enlisted posi

In the years leading up to World War II, a time when black Coast Guardsmen served mainly in food service ratings, Samuels received a variety of non-food service enlisted assignments. In 1929, the Coast Guard advanced him to chief quartermaster. This was historic in many ways. To start, he was one of the first minority individuals to achieve what was then the highest enlisted rank in the service. In addition, he was the first minority service member to serve in the quartermaster rating, one of the most responsible enlisted posi tions aboard a cutter at that time.

tions aboard a cutter at that time.

During the 1930s, Samuels left sea duty and served ashore. In 1930, he transferred to North Carolina’s famous all-black Pea Island Life-Saving Station, where he served for five years. In 1933, as part of the Federal Government’s Economy Act, the service downgraded Samuels’ rating and rank to boatswain’s mate first class. In the late 1930s, the Coast Guard transferred him to the rating of chief photographer’s mate, the first minority member to serve in that position. However, during this time, he served primarily as the personal driver for Coast Guard Commandant Russell Waesche rather than as a photographer.

In World War II, Samuels achieved several more barrier-breaking firsts in the history of the U.S. military and federal government. He was the first Latino service member to become a chief warrant officer and one of the first two black individuals to achieve that rank. Next, he received a wartime commission as lieutenant junior grade, becoming one of the first blacks to receive a commission in a U.S. sea service. The Coast Guard later promoted Samuels to lieutenant, making him one of the first blacks in the U.S. sea services to achieve that commissioned rank.

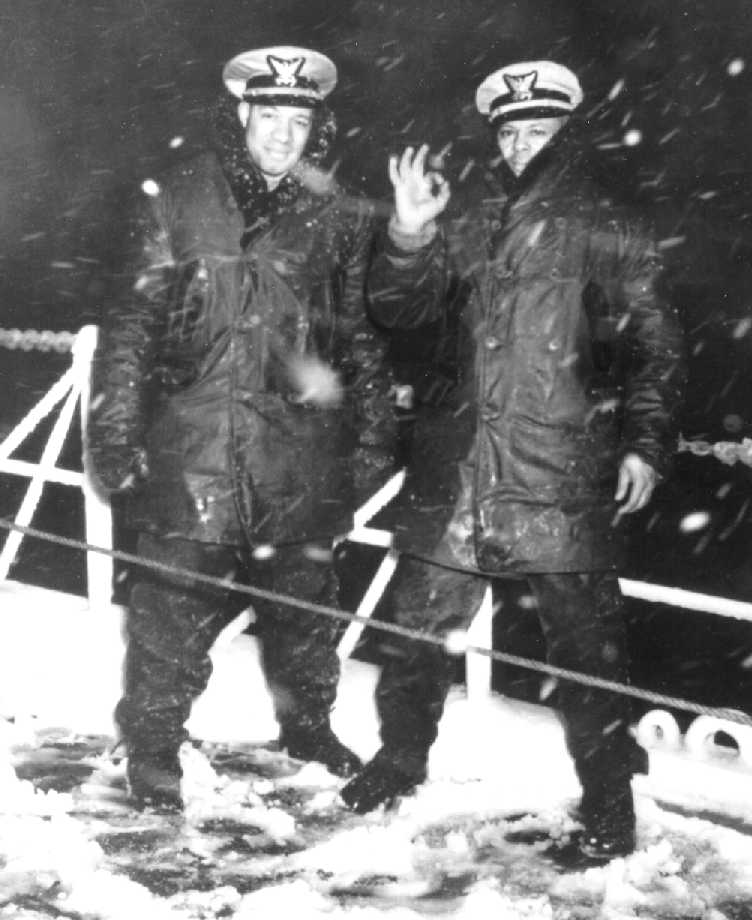

During the war, Samuels received a variety of assignments. As a chief warrant officer, he instructed recruits in signaling at the integrated Manhattan Beach, New York, Training Station. After his promotion to lieutenant junior grade, he received assignment as the damage control officer aboard the Coast Guard-manned USS Sea Cloud, the first de-segregated federal vessel in U.S. history.

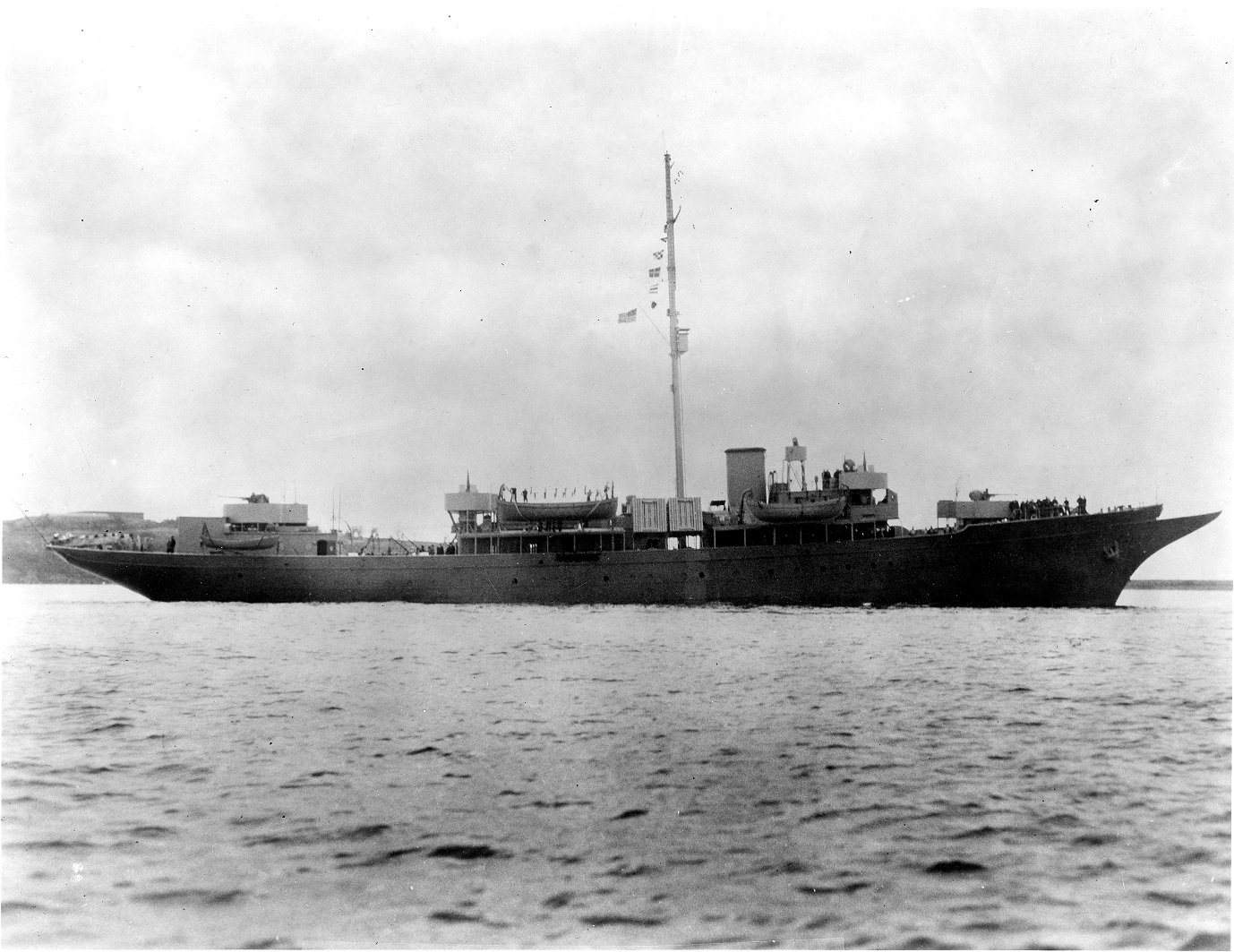

Samuels remained on Sea Cloud for a year before receiving command of Light Vessel 115, which served as an armed examination ship and net tender near his birthplace in the Panama Canal Zo

for a year before receiving command of Light Vessel 115, which served as an armed examination ship and net tender near his birthplace in the Panama Canal Zo ne. This assignment qualified him as the first black officer to command a U.S. ship in wartime as well as the first black to command a U.S. ship in a war zone.

ne. This assignment qualified him as the first black officer to command a U.S. ship in wartime as well as the first black to command a U.S. ship in a war zone.

While commanding LV-115, the service promoted Samuels to lieutenant. He next received command of LV-91, a lightship that was armed and served as an examination vessel at Key West, Florida. Not long after that, Samuels transferred to the armed 180-foot buoy tender Sweetgum, out of Miami. Sweetgum served aids to navigation and salvage missions as well as occasional convoy escort duty and submarine net tending.

As part of the Coast Guard’s postwar demobilization, the service returned Samuels to the enlisted rate of chief boatswain’s mate. For his final career assignment, he transferred to command of the buoy tender Tulip, based in Manila in the newly liberated Philippines. It was there that he retired in 1947, after a 27-year career. Several years later, he returned to the U.S. and made his home in Sonoma, California.

As an Afro-Latino service member, Clarence Samuels’ Coast Guard career proved remarkable. Not only did he serve in a wide variety of enlisted and officer roles, he broke many color barriers for blacks and Latinos in the U.S. military. Samuels’ achievements seem all the more significant in light of the fact that the first black officer to command a U.S. Navy ship took charge in 1962, nearly 35 years after Samuels did so as an enlisted man.

Clarence Lorenzo Samuels was a minority trailblazer and a member of the long blue line; and his barrier-breaking achievements led the way for minorities in all of America’s military services.