Born in the United States to parents emigrating from Mexico, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic, the first Latina women to don a Coast Guard uniform served in World War II. Some joined the Coast Guard Women’s Reserve. Others volunteered in the temporary reserve, which included both men and women. All of them released “a man to fight at sea.”

SPARS

Congressional legislation authorized the formation of the Coast Guard Women’s Reserve on Nov. 23, 1942. The women who joined were known as SPARs – Semper Paratus, Always Ready. Serving in numerous roles, SPARs were seamen, yeomen, storekeepers, radiomen, pharmacist’s mates, photographer’s mates, parachute packers, transportation specialists and many other ratings.

Hispanic-American SPARs joined for the same reasons as any other SPAR. They wanted to help their country win the war. In addition, the Coast Guard offered training they would find useful after the war. While some of the Latina SPARs’ records contain a recruiter, detailer, or recommender’s cringe-worthy statements, there is no evidence of segregation or discrimination. Those SPARs who stated their training goals met or exceeded them.

Lt.j.g. Mary Elizabeth Rivero

Lt.j.g. Mary Elizabeth Rivero

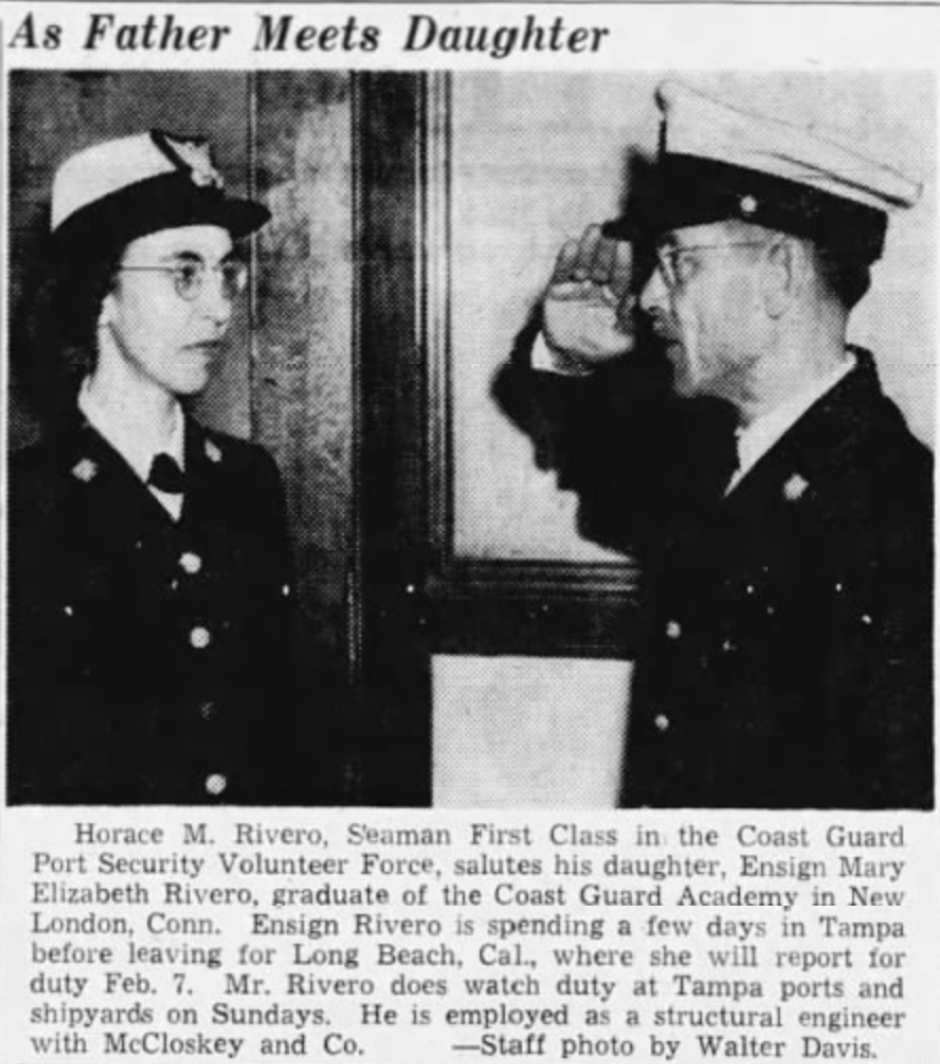

The caption read “As Father Meets Daughter.” An old newspaper photo shows stern-faced Coast Guard Temporary Reservist Horace Rivero saluting his equally stern-faced daughter, Ensign Mary Elizabeth Rivero, but he likely felt paternal pride. Horace Rivero was the son of a Cuban ambassador, and his daughter was born in the District of Columbia. The family returned to Cuba, but then moved to Florida when Mary was five years old.

Mary Rivero graduated with Home Economics and Spanish degrees from Florida State College for Women and became a teacher. Early in the war, she volunteered with Tampa’s Red Cross Motor Corps and entertained enlisted servicemen as a USO “V-ette.” Still, she wished to serve her country where she could be of greatest assistance. That meant enlisting in the SPARs on Dec. 4, 1943, and commissioning as a SPAR officer on Jan. 26, 1944. Ensign Rivero first served as a watch officer at Newport Beach, issuing boat licenses and identification, educating the public, and selling war bonds. Not long after, she took charge of the identification office at the Los Angeles Captain of the Port. She received a promotion to lieutenant junior grade and served as duty officer at the SPAR barracks in Long Beach, California, until the war ended. Rivero is the first known Latina Coast Guard officer and possibly the first female minority officer in service history.

Pharmacist’s Mate Third Class Christine Valdez

Utah native Christine Valdez loaded explosives at Ogden’s military arsenal before enlisting in the Coast Guard on Nov. 8, 1943. Her two brothers, Louis and Jimmy, were serving in the Army, and she felt that she should enlist if that would help the war effort. She told her detailer she was fluent in her mother’s native Spanish and wanted “to do some sort of linguistic work with Spanish.” The detailer made clear she would probably have to take a general assignment. Two months after reporting to Seattle, Seaman Valdez became a hospital apprentice first class at the Marine Hospital. After completing her pharmacist’s mate training there, Pharmacist’s Mate Third Class Valdez worked to keep her fellow SPARs healthy at Seattle’s SPAR barracks.

Yeoman Second Class Hope Garcia

Hope Garcia wanted to help win the war by serving as a yeoman. Volunteering in the USO and Emergency Medical Corps of the Office of Civilian Defense was not enough for her. Born in Arizona, Garcia was 31 years old when she enlisted on Nov. 28, 1943. The recruiter and detailer both commented about her accent, but that did not stop Garcia from reaching her goal. She was efficient, conscientious, and knew the Dewey Decimal library and military filing systems so well that she earned two promotions plus glowing recommendations from her supervisors at Luke Field, where she had charge of the Headquarters files. Yeoman Second Class Garcia served honorably at the Coast Guard’s district office in New Orleans.

Storekeeper Ma ria Nunez

ria Nunez

Arizonan Maria Nunez was a S.H. Kress & Co. Department Store window trimmer when she enlisted in December 1943. She requested storekeeper school and served in Cleveland after completing her training. A Coast Guard photographer snapped a photo of her trimming the barracks Christmas tree.

Radioman Third Class Nora Lopez

Radioman Third Class Nora Lopez of New York liked mechanical work. She helped her father service vehicles in his garage and operated a teletype before enlisting in the SPARs on Dec.11, 1943. The recruiter noted her pretty “Spanish” look. Lopez made it known that she wanted yeoman training or radio school, and ultimately she completed both. First, Lopez delivered dispatches, checked packages, escorted visitors, and filed confidential documents in the Intelligence Office at Headquarters. Next, she transferred to the Communications Office, where she operated a teletype and routed messages. Motivated to succeed, Lopez carried an extra duty assignment, creating value for other SPARs by teaching a Spanish class once a week. After receiving a commendation for her efforts, she was off to radio school at Atlantic City. The war in Europe ended while Lopez was in radio school. She began using her new radioman skills in New York, but she was discharged a month after V-J Day.

Storekeeper Third Class Olga Perdomo

After high school, Tampa native Olga Perdomo clerked at the Plant Field Post Exchange, selling those little necessities of life to soldiers. She enjoyed arithmetic, however, and desired office experience. A bookkeeping position  at a Chevrolet dealership followed. With the war still raging, the SPARs beckoned. Perdomo enlisted in August 1944, requesting storekeeper school. The recruiter commented, “coming from a Spanish home where the tendency is to shelter the children, it may take a little time to develop sound, wise judgment.” She continued, “...she has ideals which should be valuable to the Coast Guard.” Because Olga Perdomo was only 20, she needed her mother’s permission to join. Storekeeper Third Class Perdomo ultimately served in the supply office in New York.

at a Chevrolet dealership followed. With the war still raging, the SPARs beckoned. Perdomo enlisted in August 1944, requesting storekeeper school. The recruiter commented, “coming from a Spanish home where the tendency is to shelter the children, it may take a little time to develop sound, wise judgment.” She continued, “...she has ideals which should be valuable to the Coast Guard.” Because Olga Perdomo was only 20, she needed her mother’s permission to join. Storekeeper Third Class Perdomo ultimately served in the supply office in New York.

Seaman First Class Maria Flores

High school valedictorian Maria Esperanza Flores left Texas immediately after graduation and moved to Los Angeles. Orphaned at age 16, she worked at Hughes Aircraft Corporation to support herself. After enlisting in the SPARs on Feb. 24, 1945, Flores rode the train to the Manhattan Beach Training Station in New York. With her crackerjack skills in shorthand and typing, Flores aced the General Office Training course. The 11th Coast Guard District Office  requested a bilingual SPAR, so Seaman First Class Flores went back to California, serving in Long Beach until she was honorably discharged.

requested a bilingual SPAR, so Seaman First Class Flores went back to California, serving in Long Beach until she was honorably discharged.

Temporary Reservists

During World War II, SPARs were not the only women wearing Coast Guard uniforms. Women also joined the Coast Guard Temporary Reserve and some were of Hispanic-American heritage. Unlike SPARs, female temporary reservists were unpaid, earned no benefits, and volunteered 12 (and sometimes more) hours per week. In late June 1943, Ensign Sylvia Corral Vega and Ensign Flavia Corral took charge of female temporary reservists in Tampa, recruiting and forming the group. Women processed temporary reserve paperwork, operated the switchboard, drove male temporary reservists to their duties, prepared “chow,” and delivered it to the men on watch.

Tampa’s temporary reserve ensigns were the daughters of Manuel Corral, a Cuban-American pioneer in the cigar industry. They were members of Tampa’s social elite, and the press took just as much interest in their temporary reserve service as their social lives. Not frivolous women, the sisters felt a responsibility to do something “for the people,” said Sylvia Vega.

The total number of Hispanic-American women serving as SPARs or temporary reserves during World War II is unknown. When the United States desperately needed women to replace men at shoreside jobs so more men could fight the war at sea, these women chose the Coast Guard. Their stories bear witness to their important contributions and patriotism.