The first Native Americans known to serve in the Coast Guard were members of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head, Martha’s Vineyard, known as the Aquinnah Wampanoag. The Aquinnah Wampanoag have been considered by some the most patriotic and self-sacrificing members in the history of the Coast Guard.

The first Native Americans known to serve in the Coast Guard were members of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head, Martha’s Vineyard, known as the Aquinnah Wampanoag. The Aquinnah Wampanoag have been considered by some the most patriotic and self-sacrificing members in the history of the Coast Guard.

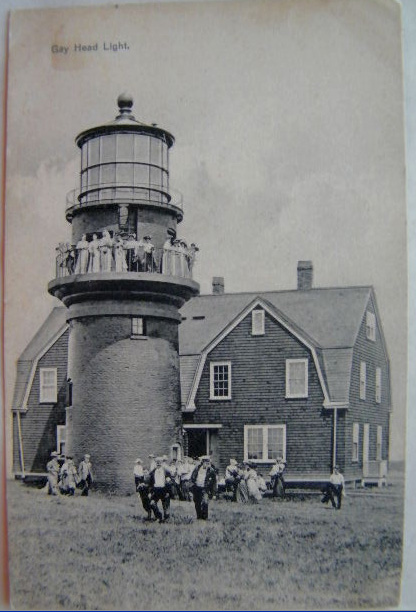

In the early 1800s, Ebenezer Skiff, the White lighthouse keeper at Gay Head Lighthouse, hired members of the Aquinnah Wampanoag to support lighthouse maintenance and operations. In an 1815 letter to his superiors, Skiff reported, “When I hire an Indian to work, I usually give him a dollar per day when the days are long and seventy-five cents a day when the days are short and give him three meals.” It became common for Gay Head keepers to hire Aquinnah Wampanoag members to assist with daily operations and maintenance. These hired assistants were the first Native Americans to serve in a Coast Guard predecessor agency.

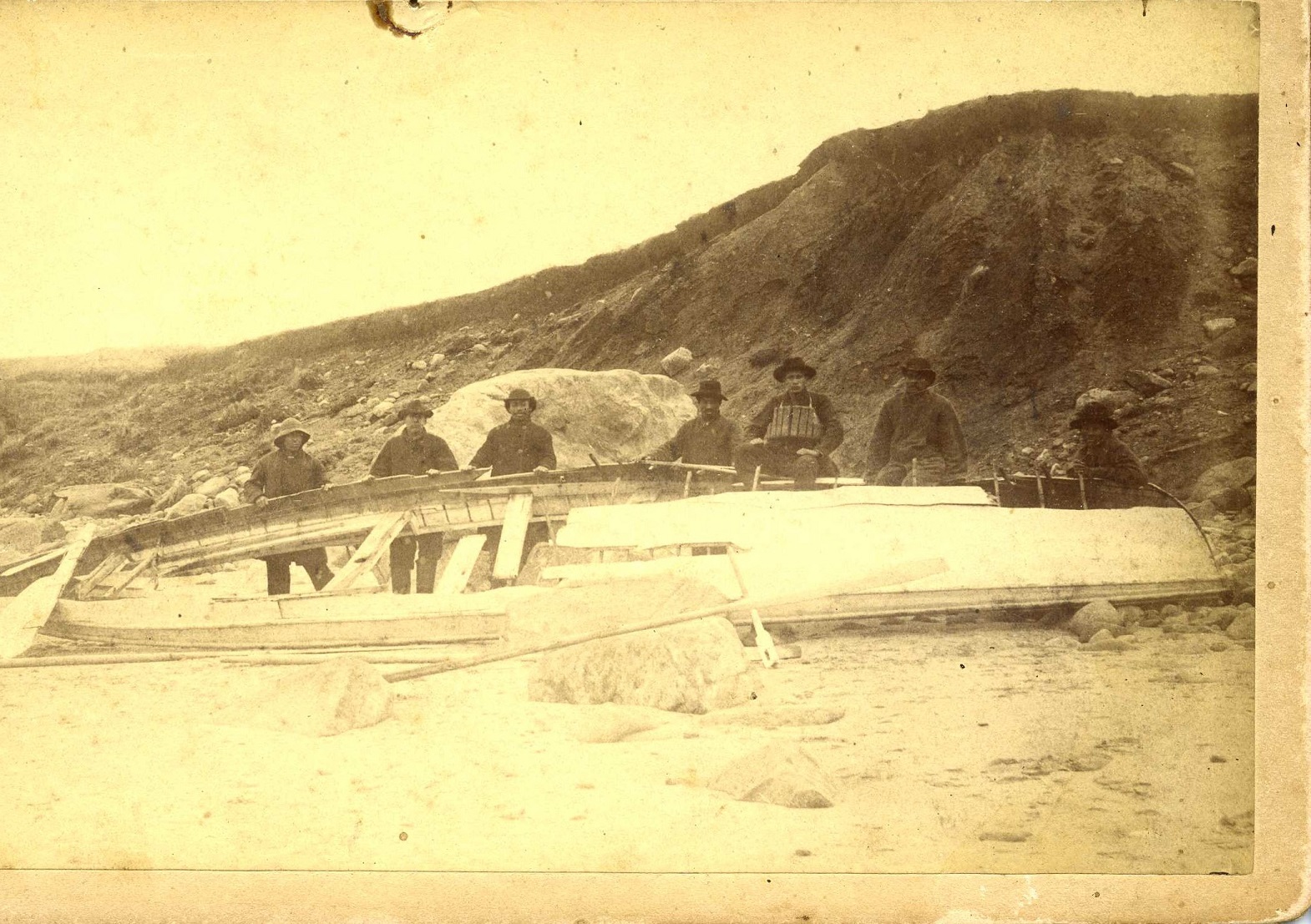

Of all events associated with early Native American service, the rescue of the S.S. City of Columbus stands out. The passenger steamer plied East Coast waters from Boston to New York and ran aground half a mile off Gay Head on a bitterly cold and stormy night in January 1884. One hundred passengers and crew drowned within 20 minutes of the grounding. Aquinnah Wampanoag volunteers assembled on shor e to brave bitterly cold temperatures and heavy seas to save any survivors. These Native American heroes manned two rescue boats, a lifeboat and a larger surfboat, provided by the Massachusetts Humane Society.

e to brave bitterly cold temperatures and heavy seas to save any survivors. These Native American heroes manned two rescue boats, a lifeboat and a larger surfboat, provided by the Massachusetts Humane Society.

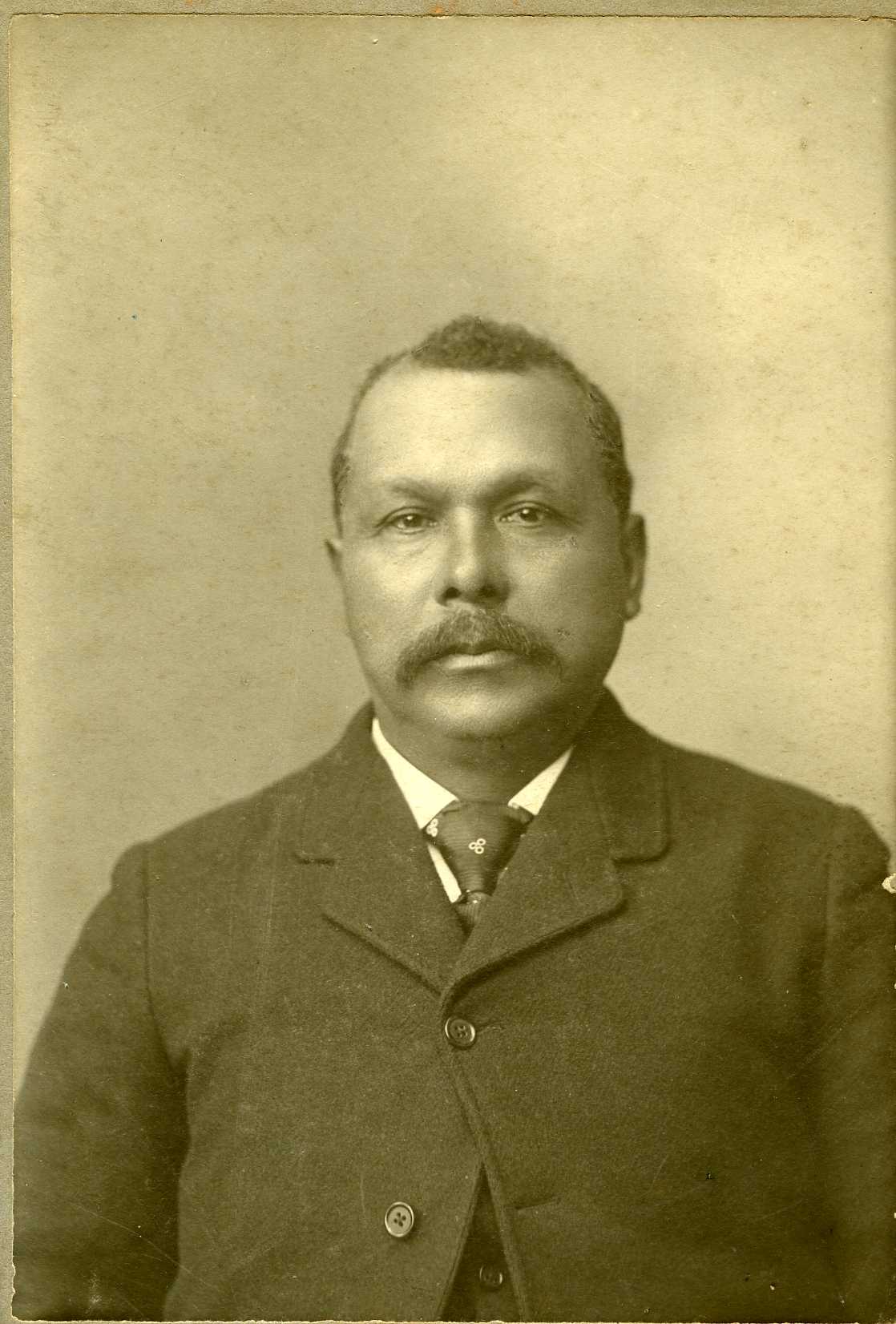

After launching into the waves, the lifeboat was crushed against the rocks and lost, but the stunned Aquinnah Wampanoag crew survived. Meanwhile, their brethren lifesavers launched the surfboat, which capsized in the heavy surf. In the bitter cold, the waterlogged volunteers drifted ashore and tried again to reach the last survivors hanging from the masts of the submerged steamer. Of these dramatic events, Aquinnah Wampanoag lifesaver Samuel Anthony later recalled, “We were on our trip to save lives or lose our own in trying.” The intrepid Native American crew righted the surfboat, retrieved seven survivors from the City of Columbus and began the return trip. Again, the surfboat overturned, however, the crew and victims got to shore safely and survived.

steamer. Of these dramatic events, Aquinnah Wampanoag lifesaver Samuel Anthony later recalled, “We were on our trip to save lives or lose our own in trying.” The intrepid Native American crew righted the surfboat, retrieved seven survivors from the City of Columbus and began the return trip. Again, the surfboat overturned, however, the crew and victims got to shore safely and survived.

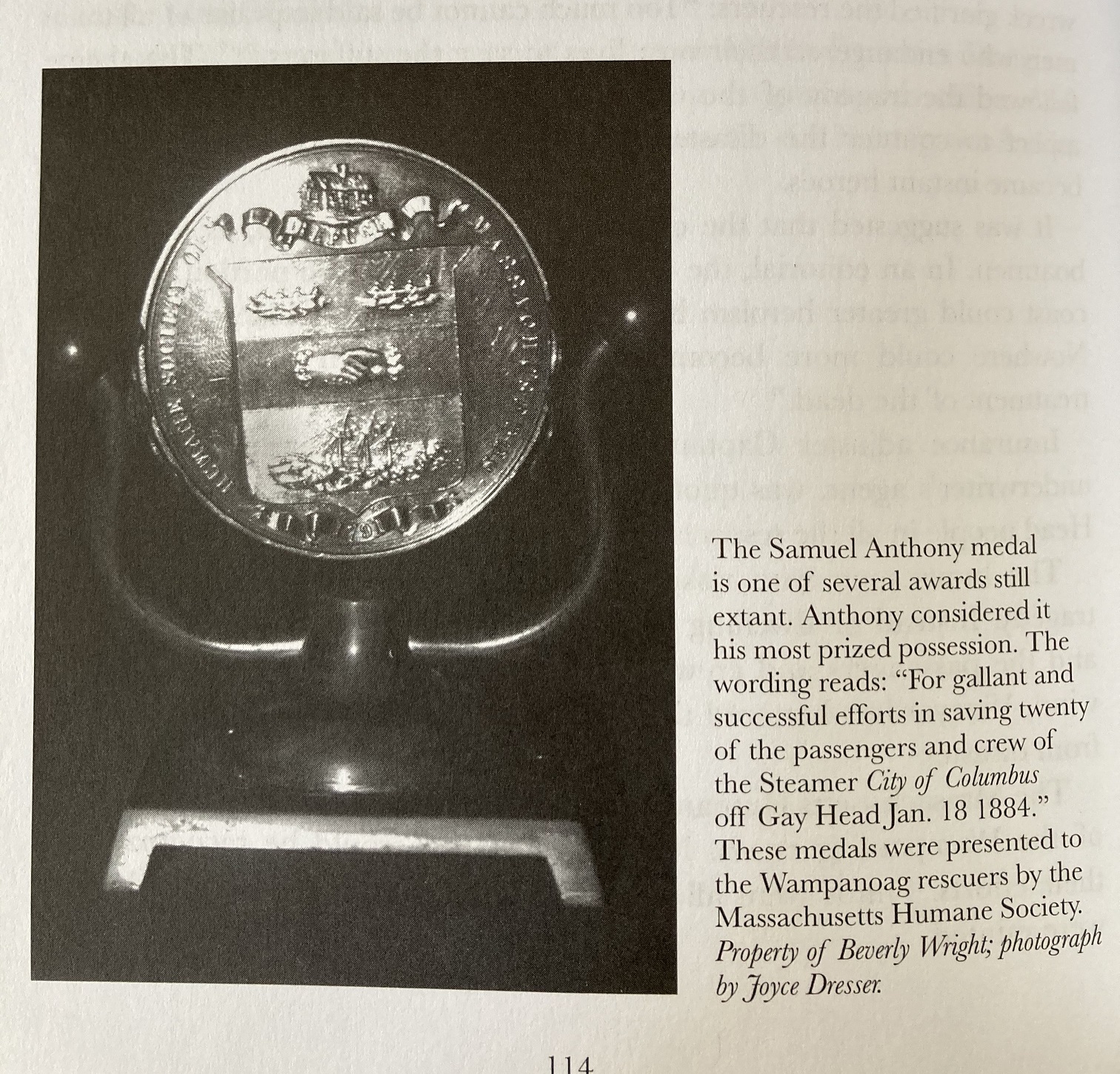

For imperiling their own live s to rescue total strangers from the wrecked City of Columbus, the Aquinnah Wampanoag men became nationally famous. Members of the all-volunteer force received high praise, medals and cash awards from the Massachusetts Humane Society. In reporting the story, the press wrote that the Native American men and their wives, who aided the victims ashore, were “deserving of all praise and the fund for their benefit and encouragement should assume large proportions. Without any expectations of reward, they periled their lives for others.”

s to rescue total strangers from the wrecked City of Columbus, the Aquinnah Wampanoag men became nationally famous. Members of the all-volunteer force received high praise, medals and cash awards from the Massachusetts Humane Society. In reporting the story, the press wrote that the Native American men and their wives, who aided the victims ashore, were “deserving of all praise and the fund for their benefit and encouragement should assume large proportions. Without any expectations of reward, they periled their lives for others.”

In 1892, the U.S. Lighthouse Service appointed City of Columbus lifesaver and Aquinnah Wampanoag m ember Leonard Vanderhoop assistant keeper of Gay Head Light. He was the first Native American to serve as deputy supervisor of a federal installation. Standing 12 feet tall and weighing several tons, Gay Head’s first-order lens was immense, incorporating more than 1,000 glass prisms. As assistant keeper, Vanderhoop’s duties included climbing the narrow spiral staircase to the lantern room and lighting the lamp at night and on low-visibility days. In the mornings, he ascended the stairs to extinguish the lamp and clean it. He was also responsible for polishing the light’s brass appurtenances, refueling the lens and resetting its lantern wicks in preparation for the next illumination.

ember Leonard Vanderhoop assistant keeper of Gay Head Light. He was the first Native American to serve as deputy supervisor of a federal installation. Standing 12 feet tall and weighing several tons, Gay Head’s first-order lens was immense, incorporating more than 1,000 glass prisms. As assistant keeper, Vanderhoop’s duties included climbing the narrow spiral staircase to the lantern room and lighting the lamp at night and on low-visibility days. In the mornings, he ascended the stairs to extinguish the lamp and clean it. He was also responsible for polishing the light’s brass appurtenances, refueling the lens and resetting its lantern wicks in preparation for the next illumination.

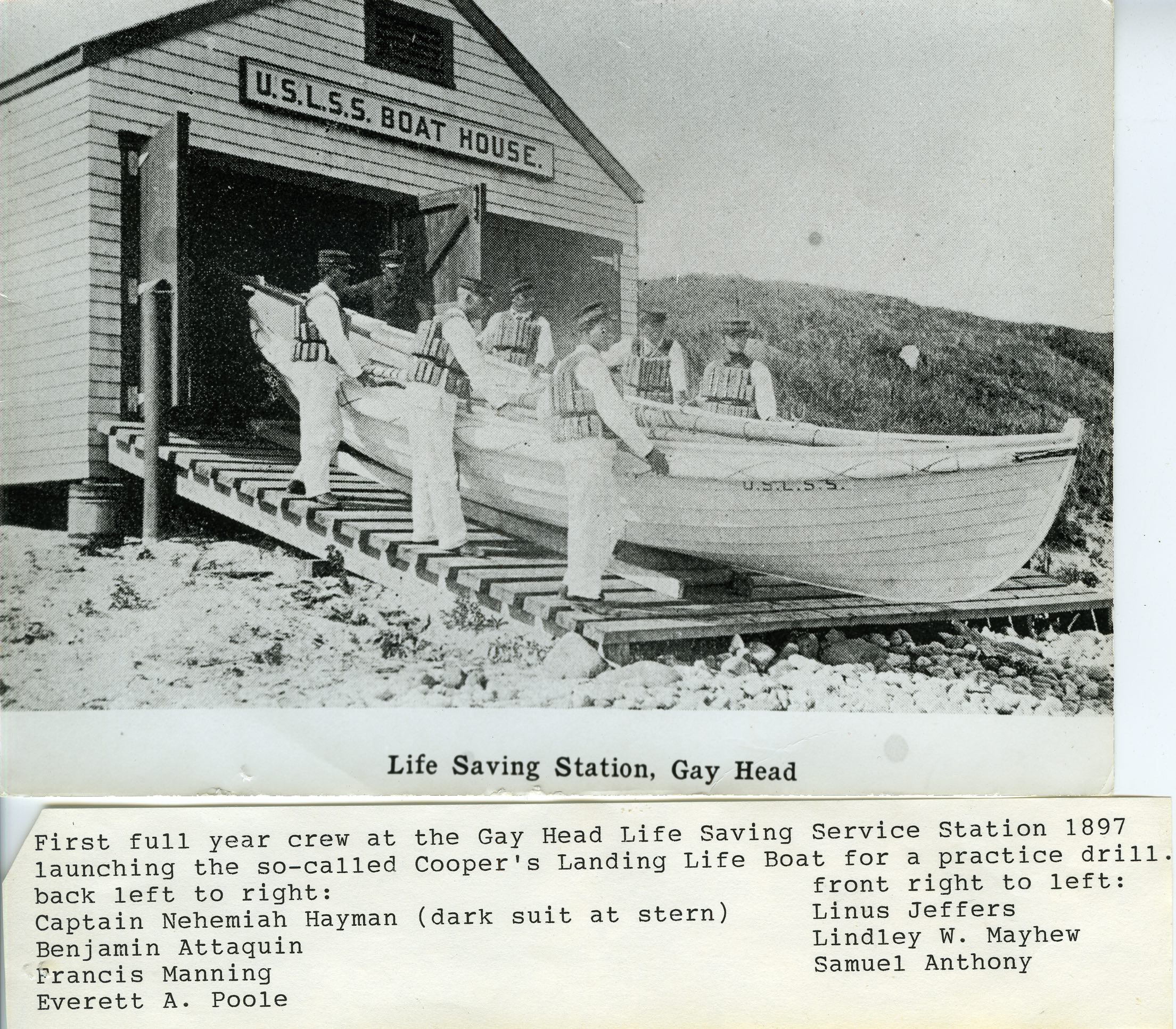

In 1895, the U.S . Life-Saving Service established a station at Gay Head with a White keeper and a crew of Aquinnah Wampanoag surfmen. One of these surfmen, 35-year-old Samuel J. Anthony, had served in the City of Columbus rescue. In January 1898, exactly 14 years after the City of Columbus disaster, the Gay Head area was hit hard by the infamous “Portland Gale,” which put ships ashore all

. Life-Saving Service established a station at Gay Head with a White keeper and a crew of Aquinnah Wampanoag surfmen. One of these surfmen, 35-year-old Samuel J. Anthony, had served in the City of Columbus rescue. In January 1898, exactly 14 years after the City of Columbus disaster, the Gay Head area was hit hard by the infamous “Portland Gale,” which put ships ashore all around Martha’s Vineyard. Two schooners grounded off Gay Head, but every time the station crew tried to launch their surfboat, heavy surf would swamp it and catapult it back at them. After more than a day spent attempting to launch, the crew managed to overcome the heavy seas and save six frostbitten crewmembers from one schooner, while the other schooner was lost with all hands except one.

around Martha’s Vineyard. Two schooners grounded off Gay Head, but every time the station crew tried to launch their surfboat, heavy surf would swamp it and catapult it back at them. After more than a day spent attempting to launch, the crew managed to overcome the heavy seas and save six frostbitten crewmembers from one schooner, while the other schooner was lost with all hands except one.

During World War I, the Aquinnah Wampanoag men of Martha’s Vineyard became nationally famous once again. The Native American community at Gay Head was honored by the State of Massachusetts as the most patriotic town in New England. Gay Head had more men serve their country by percentage of their population than any other settlement in the region. Among the 23 Aquinnah Wampanoag men who served, six were current or former members of the Coast Guard, including City of Columbu s hero Samuel Anthony, who retired in 1920 at almost 60 years of age. Between his years as a volunteer lifesaver with the Massachusetts Humane Society and as a professional lifesaver with the U.S. Life-Saving Service and the Coast Guard, Anthony’s career had spanned more than 35 years.

s hero Samuel Anthony, who retired in 1920 at almost 60 years of age. Between his years as a volunteer lifesaver with the Massachusetts Humane Society and as a professional lifesaver with the U.S. Life-Saving Service and the Coast Guard, Anthony’s career had spanned more than 35 years.

In 1919, the U.S. Navy appointed Aquinnah Wampanoag member Charles W. Vanderhoop, who was Leonard Vanderhoop’s cousin, as the principal keeper of the Sankaty Head Lighthouse on nearby Nantucket Island. He was the first Native American to oversee a federal installation. The next year, the U.S. Lighthouse Service appointed him principal keeper of Gay Head Lighthouse, naming Aquinnah Wampanoag member Max Attaquin assistant keeper. This brought national attention yet again to the Aquinnah Wampanoag men of Gay Head.

In 1919, the U.S. Navy appointed Aquinnah Wampanoag member Charles W. Vanderhoop, who was Leonard Vanderhoop’s cousin, as the principal keeper of the Sankaty Head Lighthouse on nearby Nantucket Island. He was the first Native American to oversee a federal installation. The next year, the U.S. Lighthouse Service appointed him principal keeper of Gay Head Lighthouse, naming Aquinnah Wampanoag member Max Attaquin assistant keeper. This brought national attention yet again to the Aquinnah Wampanoag men of Gay Head.

By the early 1930s, Vanderhoop and Attaquin had kept the light through many hurricanes and nor’easters and provided local shipping with years of faithful service. Over the course of their time as keepers, Vanderhoop and Attaquin provided tours for approximately 300,000 visitors, including men, women and children, as well as celebrities such as President C alvin Coolidge. However, years of climbing the tower and tending the light took their toll on Vanderhoop, and he

alvin Coolidge. However, years of climbing the tower and tending the light took their toll on Vanderhoop, and he retired on disability in 1933 after 20 years in the service. Faithful to the last, Attaquin also served until 1933, when he left the service. Later in the century, other Aquinnah Wampanoag keepers served at Gay Head Light, including Assistant Keeper Charles W. Vanderhoop, Jr., who became the first Native American son to follow his father as a service member.

retired on disability in 1933 after 20 years in the service. Faithful to the last, Attaquin also served until 1933, when he left the service. Later in the century, other Aquinnah Wampanoag keepers served at Gay Head Light, including Assistant Keeper Charles W. Vanderhoop, Jr., who became the first Native American son to follow his father as a service member.

Aquinnah Wampanoag members such as Anthony, the Vanderhoops, and Attaquin faithfully served in the Coast Guard and its predecessor services. Their dedication to the nation embodied the Coast Guard’s core values of “Honor, Respect and Devotion to Duty.”