I examined this man, and found him to be 38 years of age, strong, robust physique, intelligent and able to read and write. He is reputed one of the best surfmen on this part of the coast of North Carolina.

Lt. Charles Shoemaker, U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, 1879

This quote comes from an 1879 letter from U.S. Revenue Cutter Service Lt. Charles Shoemaker, Assistant Inspector of the U.S. Life-Saving Service, to Summer Kimball, then G eneral Superintendent of the U.S. Life-Saving Service. In the letter, Shoemaker recommended African American Richard Etheridge assume the keepership at the Pea Island Life-Saving Service Station. Shoemaker also recommended that Keeper Etheridge retain two African American surfmen already at Pea Island (W.B. Daniels and W.R. Davis), select two blacks from a nearby station and appoint two more of his choosing.

eneral Superintendent of the U.S. Life-Saving Service. In the letter, Shoemaker recommended African American Richard Etheridge assume the keepership at the Pea Island Life-Saving Service Station. Shoemaker also recommended that Keeper Etheridge retain two African American surfmen already at Pea Island (W.B. Daniels and W.R. Davis), select two blacks from a nearby station and appoint two more of his choosing.

Shoemaker wrote the letter to Kimball due to Etheridge’s distinguished reputation as a surfman and the discharge of Pea Island’s white keeper and two surfmen, whose failure to perform their duties resulted in loss of life in the wreck of schooner M&E Henderson. In the letter, Shoemaker wrote that he was “aware that no colored man holds the position of Keeper in the Life-Saving Service,” however, he explained that Etheridge was such an excellent surfman that “the efficiency of the Service at the [Pea Island] station will be greatly enhanced.” Revenue Cutter Service Lt. Frank Newcomb, another Assistant Inspector of the Life-Saving Service, also recommended Etheridge to Kimball. Shoemaker endorsed Newcomb’s letter, which stated that Etheridge “had the reputation of being as good a surfman as there is on this coast, Black or White.”

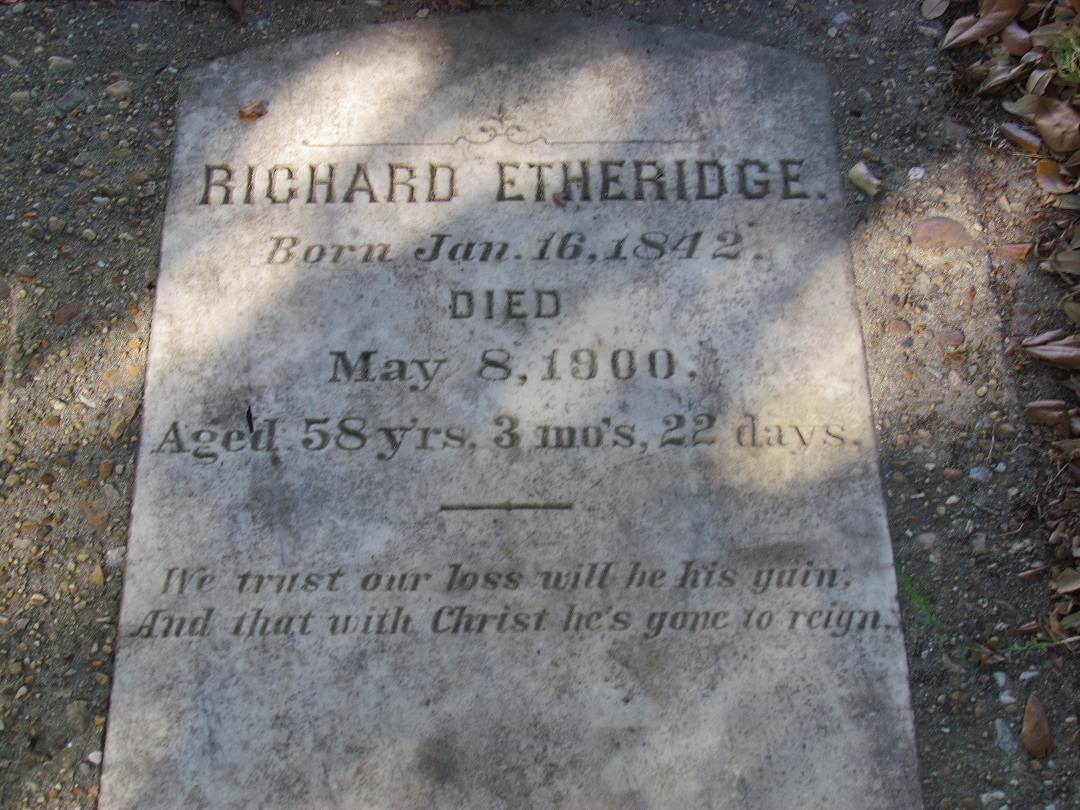

Etheridge was born a slave in 1842 and raised on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Unlike most slaves, he was taught to read and write and, at a young age, learned fishing and waterman trades. In addition, he developed a keen sense of sea and surf behavior along the Outer Banks. During the Civil War, he served for three years in the U.S. Colored Troops, getting out as a senio r ranking enlisted man. After the war, he became a leader of the African American community on the Outer Banks and began working as a Life-Saving Service surfman, first at the Bodie Island Station and then the Oregon Inlet Station.

r ranking enlisted man. After the war, he became a leader of the African American community on the Outer Banks and began working as a Life-Saving Service surfman, first at the Bodie Island Station and then the Oregon Inlet Station.

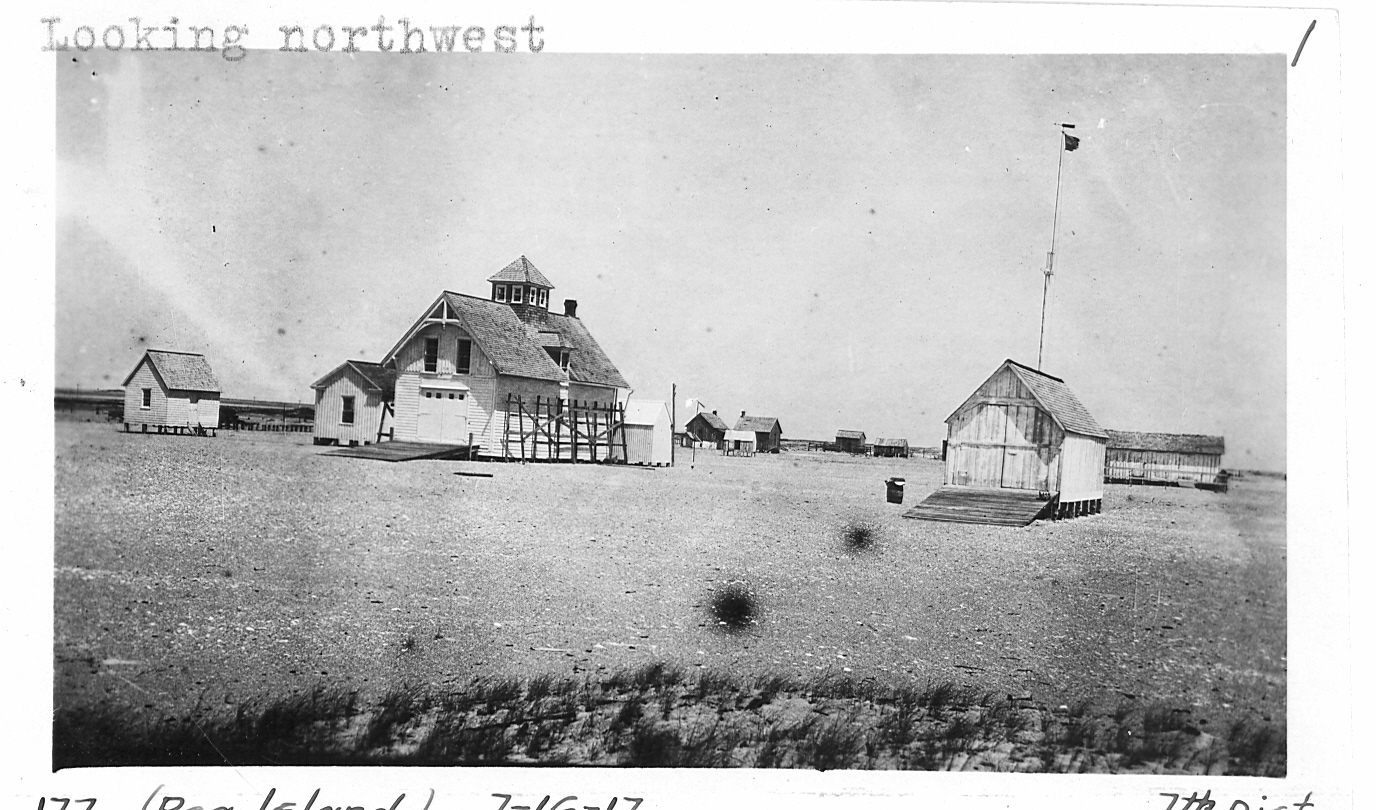

Appointed Keeper of Pea Island Station Jan. 24, 1880, Etheridge became the first African American station keeper in the service and first minority member of any kind to command a U.S. base of operations. Soon after Etheridge’s appointment, the station burned down. Determined to execute his duties to the fullest, Etheridge supervised the construction of a new station on the original site. He also developed rigorous drills that enabled his crew to tackle all lifesaving tasks. His station earned the reputation as “one of the tautest on the Carolina Coast,” and he became well-known as one of the most courageous and ingenious lifesavers in the service.

Etheridge’s training regimen proved invaluable on Oct. 11, 1896, when the three-masted schooner E.S. Newman was caught in a terrifying storm. En route from Providence, Rhode Island, to Norfolk, Virginia, the vessel was blown south, 100 miles off course, and slammed onto the beach two miles south of the Pea Island Station. The storm was so severe that Etheridge suspended the day’s usual beach patrol. However, Surfman Theodore Meekins was on lookout duty

Etheridge’s training regimen proved invaluable on Oct. 11, 1896, when the three-masted schooner E.S. Newman was caught in a terrifying storm. En route from Providence, Rhode Island, to Norfolk, Virginia, the vessel was blown south, 100 miles off course, and slammed onto the beach two miles south of the Pea Island Station. The storm was so severe that Etheridge suspended the day’s usual beach patrol. However, Surfman Theodore Meekins was on lookout duty and saw the Newman’s first distress flare through the stormy darkness, and immediately notified Etheridge.

and saw the Newman’s first distress flare through the stormy darkness, and immediately notified Etheridge.

Etheridge rounded up the Pea Island crew to brave the wind and weather. The determined lifesavers struggled to pull their surfboat to a point on the beach opposite the schooner, only to find there was no dry land. The daring, quick-witted Etheridge tied two of his strongest surfmen together and connected them to shore by a long line. The two men breeched the surf line, marched their way through the roaring breakers, and finally reached the grounded schooner. By rotating his surfmen fighting through the surf, Etheridge’s Pea Island crew ventured into the perilous waters 10 times rescuing all nine passengers and crew.

For their heroic efforts, the crew of the Pea Island Life-Saving Station, including Richard Etheridge, Benjamin Bowser, Dorman Pugh, Theodore Meekins, Lewis Wescott, Stanley Wise, and William Irving were posthumously awarded the Gold Lifesaving Medal 100 years later in 1996. The medal citation reads:

The three-masted schooner E.S. Newman, sailing from Providence, RI to Norfolk, VA ran into a hurricane. Pushed before the storm, the ship lost all sails and drifted almost 100 miles before it ran aground about two miles south of the Pea Island Life-Saving Station (NC) on 11 October 1896. The station keeper, Richard Etheridge, had discontinued the routine patrols due to the high water that had inundated the island. Surfman Theodore Meekins, however, saw what he thought was a distress signal and lit a Coston flare. He then called to Etheridge to look for a return signal. Both strained to look through the storm. Moments later, they saw a faint signal of a vessel in distress.

Etheridge, a veteran of nearly twenty years, readied the crew. They hitched mules to the beach cart and hurried toward the vessel. Arriving on the scene, they found Captain S.A. Gardiner and eight others clinging to the wreckage. Unable to fire a line because the high water prevented the Lyle Gun’s deployment, Etheridge directed two surfmen to bind themselves together with a line. Grasping another line, the pair moved into the breakers while the remaining surfmen secured the shore end. The  two surfmen reached the wreck and, using a heaving stick, got a line on board. Once a line was tied around one of the crewmen, all three were then pulled back through the surf by the crew on the beach. The remaining eight persons were carried to shore in similar fashion. After each trip two different surfmen replaced those who had just returned.

two surfmen reached the wreck and, using a heaving stick, got a line on board. Once a line was tied around one of the crewmen, all three were then pulled back through the surf by the crew on the beach. The remaining eight persons were carried to shore in similar fashion. After each trip two different surfmen replaced those who had just returned.

In recognition of the various African American crews at the Pea Island Station, including Richard Etheridge and his lifesavers, the Coast Guard commissioned the cutter Pea Island in 1992. And, on Aug. 3, 2012, the Coast Guard Cutter Richard Etheridge was commissioned in Miami, in honor of Keeper Etheridge.

As keeper of the Pea Island Life-Saving station, Richard Etheridge became one of the Coast Guard’s minority trailblazers. He rose from slavery to serve his country first in the Civil War and later in a white dominated Life-Saving Service rife with animosity toward blacks. He served as keeper of Pea Island Life-Saving Service Station for 20 years, longer than any other Pea Island keeper, and he died while serving at his post. He was the first minority officer-in-charge of any U.S. base of operations and, along with his crew, he was recognized as the first minority Coast Guardsman to receive a medal for heroism in the line of duty.