John later told me when he was swimming around in the cold dark Chinese waters and trying to signal the rescue destroyer, that he could hear the other PBM grinding around above the overcast and dropping the parachute flares that lit up the area like daylight. I wonder what the local Chinese thought was going on that night. — Commander Mitchell A. Perry, USCG (ret)

The Korean War had been underway for two and a half years and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army was fully supporting the enemy North Korea. U.S. Navy Patrol Squadron VP-22, (a.k.a. the “Blue Geese”) began its third tour of operations in the Korean theater conducting shipping surveillance of the China Sea on November 29, 1952. On January 18, 1953, a VP-22’s P2V-5 Neptune #127744 was assigned to Naval Air Station Atsugi, Japan (but, forward deployed to Naha Air Base, Okinawa), and flown by “Crew Seven”:

- LT Clement R. Prouhet - Pilot

- LT Vearl V. Varney - Copilot

- AO3 Cecil Brown – 1st Ordnanceman

- AL1 Robert L. French – 1st Radioman

- AD1 Daniel J. Ballenger – Plane Captain

- AOAN Roy Ludena – 2nd Ordnanceman

- ENS Dwight C Angell - Navigator

- AT3 Paul A. Morley – 1st Radar Technician

- AD2 Lloyd Smith Jr. – 2nd Mechanic

- AL3 Ronald A. Beahm – 2nd Radioman

- PH1 William F. McClure – 2nd Photographer

- AT3 Clifford Byars – 2nd Radar Technician

- AFC Wallace L. MacDonald – 1st Photographer

The #127744 launched on a reconnaissance mission to photograph communist anti-aircraft artillery on China’s southeastern coast. As the plane turned back toward Okinawa, ground fire from Chinese anti-aircraft positions near Swatow (now Shantou), China, struck the Neptune behind the cockpit on the left side. A battle damage assessment revealed that the radar operator, Byars, was hit with minor shrapnel wounds, the radar was inoperative, the fuel gauges were intermittent and there were two holes in the vertical stabilizer. However, the pilots noticed no issues with engine output or maneuverability. Hence, the crew sought a friendly field on Formosa (now Taiwan) for a precautionary landing to inspect the aircraft.

Suddenly, the number one engine and left wing caught fire and the vertical and horizontal stabilizers sustained further damage. They crew lost the number one engine and emergency procedures failed to extinguish the fires, which by this time had migrated to the after station. At 1230 hours, the crew issued an SOS and broadcast its intention to ditch the P2V-5.

The aircrew next reported that the left wing was almost burned through and nearing structural failure. - AL1 French reported “the port wing was burning rapidly and in short order the flap was nearly gone […] our gas tank was not far away.” LT Prouhet prepared to ditch the P2V-5 in a perilous sea state with 15-foot swells, 30-knot winds and wave crests running every 200 feet. In describing the landing, French said “the impact was slight […] considering the sea state; we had made a very smooth landing.” Fifteen minutes after it was hit by ground fire, the aircraft was in the water, but all 13 crewmembers managed to get out of the sinking plane.

Only a burned and partially inflatable eight-foot seven-man life raft was launched. Wounded by the enemy fire and shrapnel from his radar console, AT3 Byars, and the navigator, ENS Angell, were placed in the raft. PH1 McClure and AD2 Smith were separated from the main group and last seen drifting toward shore. The remaining crewmembers clung to the raft, trying to keep afloat. A P2V-5 patrolling a different sector diverted to the reported ditching position. The aircraft sighting the survivors, radioed for help, and dropped a raft but it could not be retrieved in the rough seas.

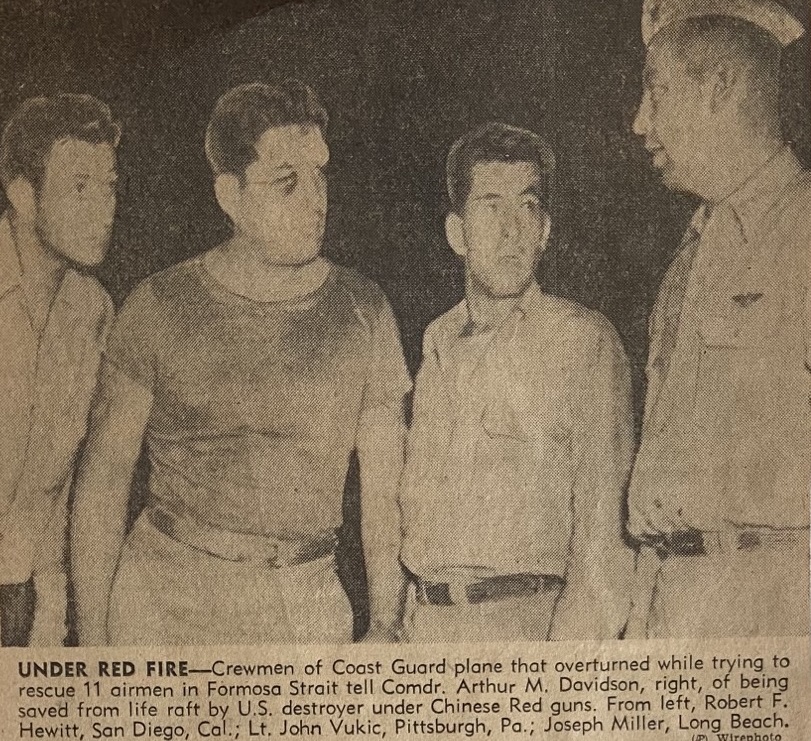

The Coast Guard Air Detachment at Naval Station Sangley Point, Philippines, received word that a Navy aircraft had gone down and were scrambled for the rescue mission. Within minutes of receiving the distress signal, Martin PBM-5G Mariner #84738, launched in response to the downed P2V-5. It was crewed by:

- LT John Vukic, Pilot

- LTJG Gerald W. Stuart, Copilot

- ADC Joseph M. Miller, Jr

- AM3 Robert F. Hewitt

- ALC Winfield J. Hammond

- AL1 Carl R. Tornell

- AO1 Joseph R. Bridge

- AD3 Tracy W. Miller

While en route, LT Vukic intercepted a radio message stating that survivors had been sighted in the water. However, the downed crew were unable to retrieve rafts or survival equipment that had been dropped from planes circling overhead.

LT Vukic descended over the surface to survey the sea conditions, but it was 1630 by the time the Coast Guard aviators spotted the P2V-5’s crew. On-scene conditions were challenging including winds of 25 to 30 knots, seas eight to 12 feet with steep crests approximately every 150 to 200 feet moving at speed of 15 knots. The water temperature was later determined to be 62°F and the survivors had been in the water for nearly five hours. Several passes were made over the survivors on a life raft, which was partially inflated with four survivors clinging to the side.

With night falling and waves rising, the AIRDET command at Sangley Point gave LT Vukic the decision of going ahead with the rescue. Considered one of the most experienced “open sea” seaplane pilots, Vukic was having extensive PBM-5G flight experience and flew PBM-5G open sea landing tests with famed Coast Guard aviator, CAPT Donald B. MacDiarmid. Lacking an arrival time for a rescue vessel and noting the perilous situation of the survivors, Vukic concluded that a landing was necessary despite the hazardous sea state and fast-approaching darkness.

LT Vukic “made a beautiful landing [even] under such circumstances” and guided the big PBM-5G close enough for his crew to fish out the sailors. The “Crew Seven” survivors were hauled aboard and wrapped in blankets. Many of the Coast Guard crewmen removed their Mae Wests to provide medical and other assistance more effectively to the injured Navy personnel. Vukic and Stuart taxied in the worsening sea state for 30 minutes but failed to locate Smith and McClure – the last two aircrew. The swells began to increase as night descended upon them and Vukic concluded it was time to depart.

The PBM-5G lifted off and the pilot actuated the amphibian’s powerful Jet Assisted Take Off (JATO) bottles to enhance climb-out. However, the number one engine suddenly failed. The dipping left wing was caught by a swell, which swept into the hull, heaved the plane upwards and caused it to cartwheel. The PBM-5G cartwheeled to the left, crashed, and broke apart. Four of the rescued sailors and five of their Coast Guard rescuers died in the crash.

Two aircraft arrived and dropped additional rafts to the survivors. Throughout the ordeal, rescue aircraft were fired upon by Chinese shore batteries. LT Vukic retrieved one raft and picked up AD1 Ballenger and AO3 Brown, while AM3 Hewitt retrieved the second raft and gathered Prouhet, Varney, Ludena, McDonald, and French. The USS Halsey Powell (DD-686) – a 376-foot Fletcher-class destroyer commanded by CDR Albert Sidney Freedman, Jr., USN – finally arrived on the scene after the downed flyers had been in the water for seven-and-a-half hours.

A second Coast Guard PBM-5G, #84722, from Sangley Point, piloted by LT Mitchell A. Perry with LT Frank Parker as co-pilot and LTJG Charles Fischer as third pilot and navigator, arrived after dark and dropped 34, one-million candlepower parachute flares to assist the destroyer navigating Chinese coastal waters. Squalls increased in intensity and visibility was now less than 700 feet. The seven survivors in the second raft had used all but one signal flare. The last flare successfully signaled their position to the destroyer. Eventually, as the ship approached, two swimmers deployed from Halsey Powell, swam to the raft and secured a line, and the survivors were pulled aboard.

Meanwhile, the first raft containing LT Vukic had drifted to within 200 yards of Narnoy Island. USS Halsey Powell found itself in less than six fathoms of water, navigating over uncharted barrier reefs. Demonstrating outstanding seamanship, CDR Freedman maneuvered the destroyer around the reef, so the ship sailed parallel to the coastline with less than 200 yards of margin for error. LT Prouhet remarked, “this feat of seamanship was accomplished in poor visibility on a murky night using charts of doubtful accuracy […] --it took courage.” Vukic, Ballenger, and Brown were finally rescued just before midnight.

Of the 21 men from both aircrews, only ten survived, including seven Navy aircrew and three Coast Guard aircrew. The following perished in the crash:

- ENS Dwight C Angell, USN

- AT3 Paul A. Morley, USN

- AL3 Ronald A. Beahm, USN

- AT3 Clifford Byars, USN

- LTJG Gerald W. Stuart, USCG

- ALC Winfield J. Hammond, USCG

- AL1 Carl R. Tornell, USCG

- AO1 Joseph R. Bridge, USCG

- AD3 Tracy W. Miller, USCG

PH1 William F. McClure and AD2 Lloyd Smith, Jr. were lost after the initial crash, and they remain unaccounted for. Based on all information available, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) assessed the individual’s case to be in the analytical category of “non-recoverable”

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

— “For the Fallen” by Laurence Binyon

The Coast Guard PBM-5G aircrew was awarded the Gold Lifesaving Medal for their heroic actions.

The armistice was signed six months later on July 27, 1953, and was designed to “ensure a complete cessation of hostilities and of all acts of armed force in Korea until a final peaceful settlement is achieved.” This year marks the 70th anniversary of the events that transpired in the Formosa Straits – we remember the courageous Coast Guard and Navy men who perished and the families and comrades they left behind.

-USCG-

Editor's Note: Retired CAPT Sean M. Cross served 25 years in the Coast Guard as a helicopter pilot and aeronautical engineer. Flying both the MH-60T and MH-65D, he accumulated over 4,000 flight hours while assigned to Air Stations Clearwater, Cape Cod, San Diego, Elizabeth City (NC), and Traverse City (MI), which he commanded.