The Coast Guard established the “Ancient Mariner” Award in 1978 to honor the officer and enlisted Cuttermen who personify the dedication and professionalism associated with long service at sea and have held the distinction of Cutterman longer than any other officer or enlisted member. Upon retirement, the Ancient Mariner Award is passed to the next qualifying person. Although it was decades ago, I can well remember the sense of awe and respect I felt as a junior officer when I learned that one of my bosses was the service’s Ancient Mariner!

Today, federal law sets mandatory military retirement ages. For the Coast Guard, most personnel must retire at age 62, while cases with presidential waivers may retire at age 68. However, in 1893, there were no mandatory retirement laws. That year, 93-year-old Captain Francis Martin was the oldest commissioned officer in the United States Revenue Marine Service. He was also older than any other officer in the U.S. Navy. As there was no retired list for the Revenue Marine at the time, he was still considered on active duty, awaiting orders. He would remain on active duty for another two years, when a retired list was established. One of Captain Martin’s contemporaries, U.S. Navy Admiral Thomas Selfridge (1804-1902) held the record for longest serving mariner, with 83 years of active duty. Captain Martin started late, so he ended up with “only” 63 years of active service.

![A published engraving showing Captain Francis Martin later in life. (Kansas City [Missouri] Journal, May 22, 1898) A published engraving showing Captain Francis Martin later in life. (Kansas City [Missouri] Journal, May 22, 1898)](/Portals/6/LBL/Ancient Mariner/7_ Martin headshot.jpg?ver=uCK5sp5XXBdVDUIHvuHH3w%3d%3d)

Witnessed Napoleon’s Funeral

Captain Martin was born on June 4, 1800, in New York. He first went to sea at the age of 12, serving under his uncle who was a ship’s captain. While still a teenager, Martin’s voyages included a visit to St. Petersburg, Russia.

In 1821, Martin was still serving under his uncle as second mate of the ship Purington, sailing from Java to Holland. Short of fresh vegetables, the ship stopped off at the South Atlantic Island of St. Helena. The stop happened to coincide with the funeral of the island’s most famous resident: exiled Emperor of France, Napoleon Bonaparte. In his most frequently retold story, Martin remembered a simple ceremony: A coffin with the sword and hat of Napoleon carried to the grave by marines; a few brief prayers and a soldier’s salute closed the ceremony. Martin was one of the few Americans to witness the funeral.

Commissioned in the U.S. Revenue Marine

Martin was commissioned into the Revenue Marine by President Andrew Jackson as a 3rd Lieutenant. He was listed on board the (sailing) Revenue Cutter Rush as early as 1830, however, his officer’s commission was confirmed by official documents in 1833.

Available records are unclear about how long Martin was assigned to the Rush, but in January 1831, the cutter was wrecked in a winter storm on the north shore of Long Island at Huntington Bay. After dragging its anchor, the ship grounded heavily. Rush’s captain, Oscar Bullus, later wrote “The Rush struck so heavily that I lost all hope and ordered the masts to be cut away to light the vessel.” The crew was unable to do this “as the weather was intensely cold, and everything covered with a perfect sheet of ice.” Fearing the ship would break up, Bullus ordered the boats to be launched, and the ship abandoned. Fortunately, the crew all made it ashore and took shelter in a local farmhouse. The Rush ended up “high and dry at low water, having worked over the rocks and bilged.”

Action in the Seminole War

By 1836, Martin served as a 2nd Lieutenant assigned to Revenue Cutter Washington at Key West, Florida. In January 1836, he learned of the “Dade Massacre” north of Fort Brooke (near modern Tampa, Florida), resulting in the deaths of all but three of 110 soldiers in an ambush by Seminole Indians. By the direction of the president, the Washington was put under orders of the Secretary of the Navy to cooperate with the removal of the Seminoles. The Washington sailed immediately for Tampa Bay, where two 12-pounder canon, two officers, and ten men were landed to defend the post from an expected Indian attack on the 200-man garrison. The waters near shore were too shallow for regular U.S. Navy ships, so the Washington was positioned to guard both the fort and a small fleet of transport ships filled with civilian refugees. Once reinforcements arrived, the Washington was next ordered to make a reconnaissance of the west coast of Florida.

The logbook of the Washington from February 13, 1836, recounted an event involving 2nd Lieutenant Martin:

Reached Tampa Bay in the morning. At 12:30 p.m., we heard several great guns on the land apparently abreast of us, we being about 3 miles from the beach of the southeast side of the Bay, say 28 miles from Fort Brook (sic). Shortly after saw two canoes full of Indians, who appeared to be retreating from the scene of action. We gave chase to them and fired a 12 pounder at them loaded with round shot, at the same time our gig, crew and Lieutenant Martin in pursuit of them. At 1:30, came to anchor and dispatched all our boats and officers, except Lieutenant Clarke, who was left in charge of the Cutter. The canoes hove to, after having been fired on several times. They proved to be friendly Indians belonging to Captain Bunces Rancho. Let them pass and returned to Cutter.

In 1845, while serving as the commanding officer of the Revenue Cutter Ewing at New York, Martin received perhaps the greatest complement a Coast Guard officer could receive. Local papers reported that his ship got underway during a severe storm, only returning to get provisions, and then sailing back to sea:

Such noble conduct reflects great credit on the officers of the Ewing, and when compared with that of others who have been placed in similar situations, and who, in most instances, have proved to be only ‘fair weather cruisers,’ will be gratefully remembered by our mercantile marine.

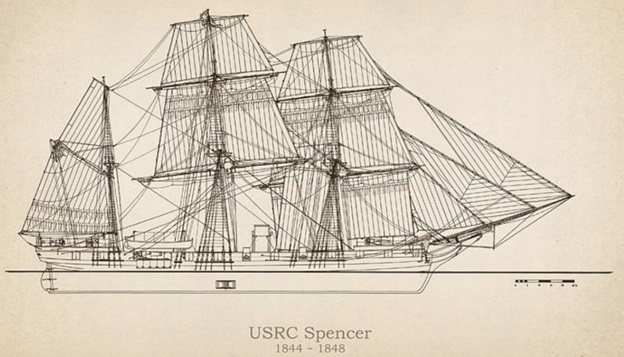

From the Ewing, Martin transferred to the new iron steam cutter Spencer as the ship’s 1st Lieutenant, the second highest ranking officer. Duty on the Spencer was very challenging because the ship used an experimental horizontal paddle wheel called a “Hunter Wheel.” The design was ineffective, and the ship’s engines frequently broke down.

Served in the War with Mexico

When war broke out with Mexico in 1846, the Spencer was ordered to the Gulf of Mexico as part of a squadron to support the Army’s movements in Mexico. But on its way south, engine problems caused the ship to turn back for repairs. Martin eventually made his way to the Gulf where he served as 1st Lieutenant on Revenue Cutter Oliver Wolcott. In the summer of 1846, the Wolcott provided messenger service carrying important dispatches between government officials in Mobile, Alabama, and Army commanders operating in Mexico. Through this duty, Martin became acquainted with General Winfield Scott and other famous military leaders of the Mexican war.

Commanded a Lightship

One of Lieutenant Martin’s more unusual ship commands occurred in late 1846. According to newspaper reports, “The schooner Sand Key, intended as a light boat, arrived here [Key West] to-day under command of Lieut. Martin of the revenue service. She will shortly be placed at her moorings.” Revenue Marine officers served in at least one other instance of moving a lightship from one station to another, prior to being lit under the command of a lightship keeper. Martin took command of the lightship only to transport it, at lightship keeper’s pay, which was only $700, much less than the $960 he would earn as a 1st Lieutenant in the Revenue Marine. A few weeks later, Sand Key Lightship, equipped with a single lantern about 25 feet high placed in its middle, was activated a few miles southwest of Key West, Florida.

Explored the Everglades

Two years later, Martin was back aboard the Wolcott under orders to support a survey of the Florida Everglades. Martin not only provided lead surveyor Buckingham Smith with transportation and boat crews to conduct the five-week-long survey, but he also accompanied Smith on many of the boat trips into Florida’s interior. Smith’s report to the U.S. Senate is now considered the first official publication on the area.

In 1850, Martin became involved in a salvage case of national significance. Former Vice President John C. Calhoun was a staunch State’s Rights and pro-slavery advocate whose most famous act was a written speech advocating the right for states to secede from the Union. Calhoun’s popularity, especially in his native South Carolina, caused the City of Charleston to commission a life-size marble statue from the great American sculptor, Hiram Powers. The statue was completed at Powers’ home in Rome, Italy, and shipped to the U.S. in 1850, shortly after Calhoun’s death from tuberculosis at the age of 67. Unfortunately, the ship Elizabeth carrying the statue to the U.S., sank off Fire Island, New York. Captain Martin, now commanding Cutter Morris in New York, was credited with finding the wreck of the Elizabeth six weeks after she had sunk. It took another ten weeks before a diver with a newly invented diving suit could raise the slightly damaged statue. The statute later stood in Charleston’s city hall until it was destroyed during the Civil War.

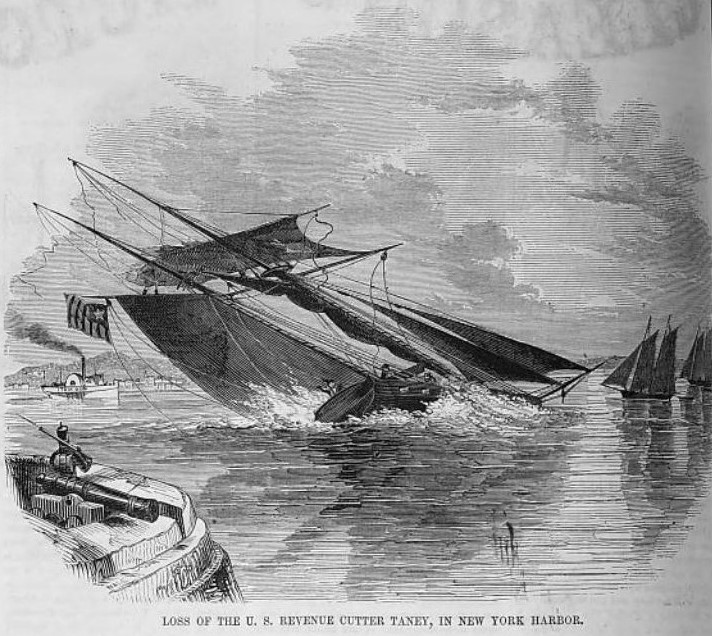

The Sinking of Revenue Cutter Taney

Records show that Francis Martin was promoted to Captain in the Revenue Marine on October 1, 1851. The next year, on August 3, 1852, Martin experienced perhaps the worst day of his life. While commanding officer the Revenue Cutter Taney sailing in New York Harbor, Martin saw an approaching band of storm clouds and went below to get his overcoat. Within seconds, the ship lurched onto its side, quickly filled with water, and sank. Martin fought his way out of the flooding ship where he and most of his crew were quickly rescued by a passing steamboat.

The ship was the victim of what was called a “white squall” or what would today be called a “microburst.” This is a condition where a storm causes a strong localized downdraft. Other sailing ships 150 yards away witnessed the sinking but reported no wind from the storm. The case was so unusual and well documented by nearby ships that the Taney’s sinking was recounted in several books about the weather at sea. No fault was assigned to Captain Martin, and the event had no impact on his career. The Taney was raised from the shallow waters and returned to service. Unfortunately, five members of his 15-man crew were killed and two seriously injured. After commanding the Taney, Martin took command of the Revenue Marine Brig Washington at New York, and later Cutter Ingham at Detroit.

Fought for Equal Benefits of Revenue Marine Officers

On at least two occasions, Captain Martin petitioned Congress to give members of the Revenue Marine the same privileges as members of the U.S. Army and Navy. The first petition involved pay. In the 1830s, Revenue Marine officers received less pay than members of the same rank in the U.S. Navy. Due to the Revenue Marine’s past service in cooperation with the U.S. Navy during the Quasi-War with France (1798-1800), Congress set policy providing equal pay during wartime for duties of the same rank and responsibility.

One example of this was Revenue Service Captain Ezekiel Jones’ service in 1836 commanding the Revenue Cutter Washington at Tampa Bay as previously discussed. The Washington was put under U.S. Navy orders while Francis Martin was on board. In 1838, Captain Jones petitioned Congress for additional pay (at the Navy rate) for his service during the war. Congress the petition in 1839, with Jones receiving an additional $900 for his service.

Following on his commander’s success, Martin petitioned Congress in 1840 for his additional pay for the same 1836 voyage. Martin’s petition took years to work its way through the government. It was denied in 1842 and finally discharged by the Senate in 1848.

In 1860, Martin petitioned for members of the Revenue Marine Service to be admitted to the Institution of the Insane of the Army and Navy in Southeast Washington, D.C. This time, Congress reacted favorably, passing an amended act, so sick Revenue Marine personnel could be admitted as patients. The Institution of the Insane later became St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. In 2013, to reutilize the largely abandoned facility, the U.S. Coast Guard moved its headquarters to the St. Elizabeth’s Hospital grounds.

Last Afloat Command

After the Civil War, Martin began commanding several vessels on the Great Lakes. Beginning in 1872, at age 72, Captain Martin commanded Revenue Cutter Fessenden. The Fessenden was a 180-foot-long sidewheel steamer built in 1869 and home-ported in Cleveland, Ohio. The Fessenden would patrol shipping lanes on the Great Lakes during the active shipping season and lay up from December through April. Each winter, her crew was discharged and a new crew hired in the spring. In 1875, the Fessenden was ordered to a new homeport in Detroit. In 1876, Captain Martin turned over command to a new captain and was assigned the status of “waiting orders” status.

Records for Martin’s shore duty stations have not been found. However, a report compiled in 1875, well before his retirement, lists the following:

How long in the service: 42 years, 0 months

Total sea service: 32 years, 0 months

Shore or other duty: 2 years, 9 months

Unemployed (awaiting orders): 7 years, 3 months

.jpg?ver=uCK5sp5XXBdVDUIHvuHH3w%3d%3d)

Family Life

In between his shipboard assignments, Captain Martin had time for a family. He married twice, first to Rachel Brown Martin (1805-1858) and later to Jane Garretson Clawson Martin (1835-1902, married in 1861). He was the father of at least four children: Mary A. (1830-1850), Louis Marin (1835-1917), Jessie Poillon Martin Bleakley (1868-1958) and Eugene B. Martin (1871-1880). Note that when son Eugene was born, his older brother was already 36 years old.

Passing of a Legend

In 1895, the service enforced an act that transferred Martin from active duty to the retired list. He was 95 years old with an official record of 63 years as a commissioned officer. After he retired, Martin remained vigorous. When he was 98 years old, he weighed 175 pounds, and he was an avid reader fond of poetry, especially the works Byron, whom he quoted extensively. Martin claimed he was never sick in his life until he was 71 years old, when he suffered an attack of typhoid fever. Other than hearing loss, he remained in good health after leaving the service.

On January 26, 1901, he caught a cold and took to his bed. He was attended by his son Dr. William Martin, and his son-in-law Dr. C.E. Bleakey at his home in downtown Detroit, located only a block from the shipping channel of the St. Clair River. Despite the loving care he received, his condition gradually worsened, and he died on January 31, 1901, at the age of 100. He was interred at Detroit’s Elmwood Cemetery.

Incredibly, during Martin’s career, he served on or commanded the following vessels: As a civilian, he served aboard the Brig Vigilant (1814) and the ship Purington (1821). In the U.S. Revenue Marine, he served on cutters Rush (1830), Madison (1833), McLane (1834), Dallas (1835), Ingham (1836), Washington (1836), Dexter (1837), Madison (1837), McLane (1837), Crawford (1841), Van Buren (1842), Ewing (1843), Spencer (1845), Sand Key Lightship (1847), Wolcott (1847), Ewing (1847), Morris (1850), Taney (1851), Washington (1853), Ingham (1854), Corwin (1861), Bibb (1861), Agassiz (1861), Tiger (1862), Forward (1862), Toucey (1863), Andrew Johnson (1866-1870), Sherman (1870), and Fessenden (1872-1876). Not counting multiple assignments to the same ship, that totals 24 cutters as a Revenue Marine officer alone!

More than just living to a ripe old age, Captain Martin lived a full life that reflected the many missions and highest traditions of today’s Coast Guard. With 63 years of service in the Revenue Marine, Francis Martin became the Coast Guard’s all-time Ancient Mariner. Captain Martin, I salute you and thank you for your service!

-USCG-