The United States Coast Guard’s predecessor service of the U.S. Revenue Marine played a unique role in the 19th-century technological transition from wood and sail to iron and steam. During the late-18th and early-19th centuries, all forms of mechanized technology saw a sea change in motive power and construction materials. Medieval forms of maritime technology associated with wood and wind energy succumbed to iron and steam power.

In the mid-19th century, military technology witnessed rapid technological change with inventors focusing on naval technology in the years leading up to the American Civil War. These men applied steam and iron to machines of war, such as semi-submersibles, rams, heavy ordnance, mines, spar torpedoes and ironclads. The Civil War-era gunboat E.A. Stevens served as an example of the Revenue Marine’s support of new naval technology and became the most unique cutter in the history of the U.S. Coast Guard.

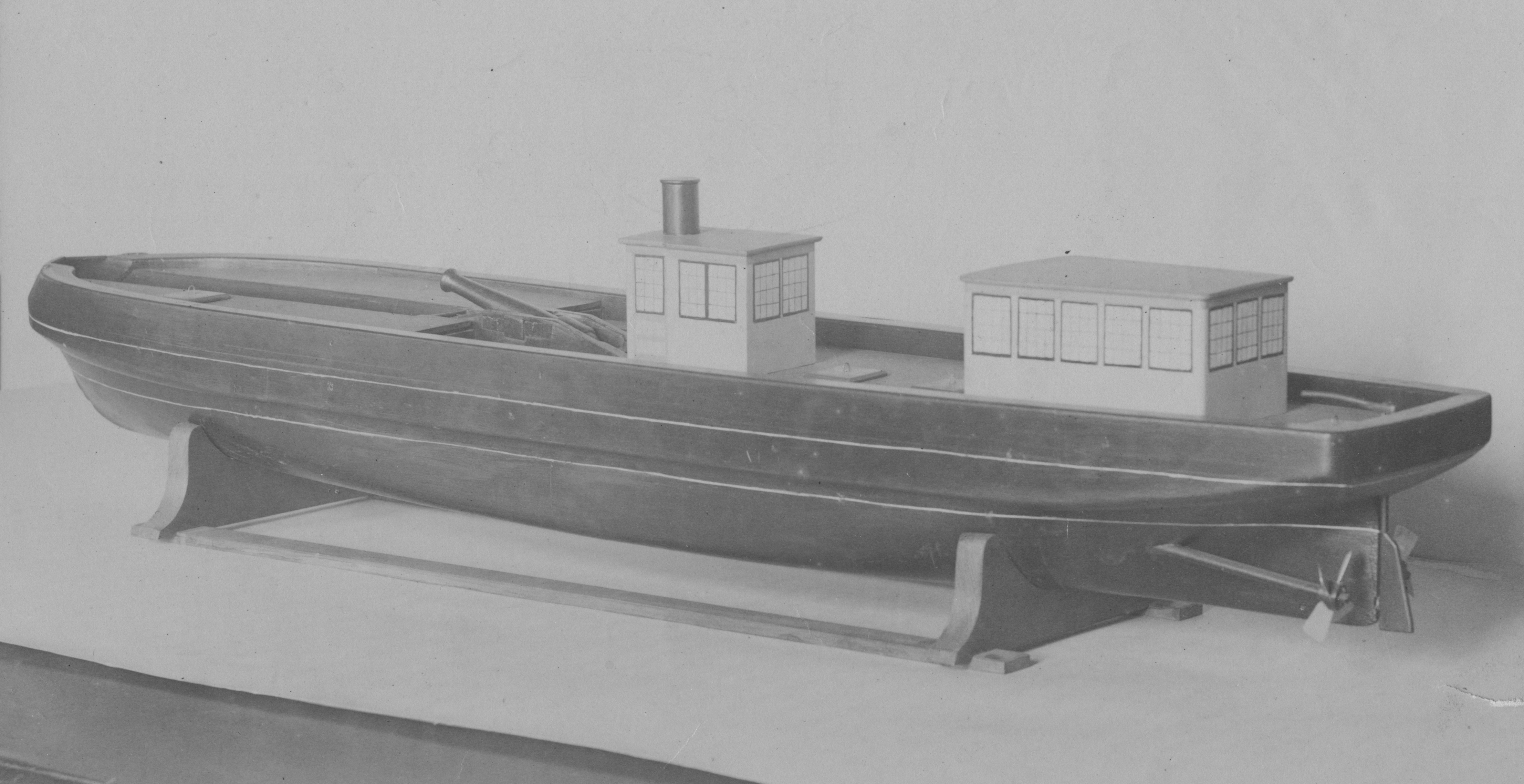

In the late 1830s, inventor Edwin A. Stevens developed a gunboat to operate in shallow water. He incorporated ballast tanks located both fore and aft in the vessel’s iron hull. The tanks used a patented gum elastic liner Stevens used to ensure a watertight seal. These ballast tanks made the Stevens a semi-submersible, allowing the vessel to submerge up to three feet to an overall depth of nine feet. This lowered the gunboat’s profile, minimized the vessel’s exposure to cannon fire and placed the vessel’s vulnerable steam machinery below the waterline. Stevens equipped the tanks with heavy-duty centrifugal pumps that could fill the tanks with water in just eight minutes. Conversely, if the gunboat ran aground while ballasted, pumping out the tanks could float her in minutes. And, by pumping the ballast tanks dry, the gunboat doubled her speed from five knots to ten.

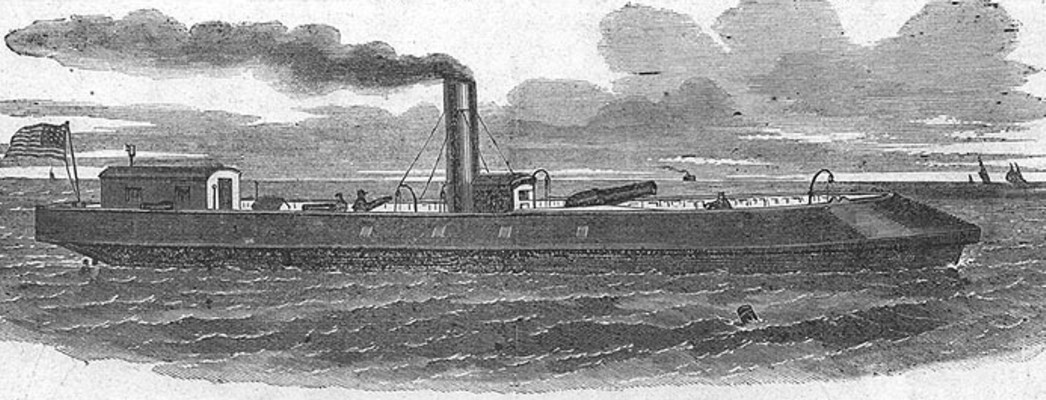

The E.A. Stevens had deckhouses located amidships and on the after deck of the gunboat. Positioned forward of the smokestack, the pilothouse served as the captain’s station while underway. Before entering a war zone, the crew attached boilerplates to the pilothouse as protection against musket fire. The after deckhouse served as the galley and quarters for the three officers and received iron plating as well. The vessel’s enlisted crew of 20 men slept below decks in a compartment located between the engine room and the forward ballast tank. Their quarters also served as the loading room for the main gun during combat.

The Stevens came equipped with little armor and only a few guns. Besides her deckhouses, her only armor consisted of a low-lying angled armor band or skirt surrounding the main deck. The band covered a wooden bulwark built of solid cedar, which rose 18 inches above the deck and measured four-and-a-half feet in depth. The bulwark surrounded the deck, keeping water off it and providing cover from enemy fire. The gunboat carried three cannons, including two 12-pound Dahlgren howitzers mounted on a pivot on each side of the gunboat. In addition, the Stevens received the first 100-pound rifled Parrott gun produced for Union military forces. The diminutive vessel sported a unique muzzle-loading system in which the rifle’s muzzle pivoted down to an opening in the vessel’s forward deck where the crew could load it below decks. An alternative to the new armored turret system, the gunboat’s cannon could be loaded under the deck in 25 seconds without exposing the gun crew to enemy fire. And Edwin Stevens’s patented India rubber gun suspension system absorbed nearly 15 inches of the main gun’s recoil.

The Stevens’s new technology also included an innovative propulsion system. The Stevens family had pioneered the development of the twin-screw system since the beginning of the 1800s and it made sense to test that technology under combat conditions. With twin propellers, the Stevens gunboat could revolve full circle within her own length in only two minutes. The gun carriage was fixed laterally, so the twin-screw arrangement allowed the captain to train the gun using the gunboat’s helm and propellers. And, with her top speed of ten knots, the Stevens could serve as a dispatch vessel for delivering wounded men and important messages.

Stevens offered the E.A. Stevens to the Union Navy free of charge, but the Navy declined his offer due to the vessel’s unconventional technology. Stevens turned to the Revenue Cutter Service, which welcomed the opportunity to operate its own steam-powered gunboat. In the middle of March 1861, the Treasury Department ordered the gunboat to head south from New York to Hampton Roads. She did so with a crew of over 20 enlisted men that included a boatswain, gunner, carpenter, steward, cook, two quartermasters, 14 seamen and a “servant.” On April 9th, 1862, the Stevens steamed into Hampton Roads, the Union Navy’s base of operations, to join the James River Squadron.

On April 11th, E.A. Stevens began combat operations exchanging fire with CSS Virginia, when the Confederate ironclad emerged from her anchorage near Portsmouth, Virginia. Virginia’s primary target, USS Monitor, declined action, so the hostilities proved inconclusive. On the 29th, Revenue Marine lieutenant, David Constable, took command of the gunboat and her crew. By the time he assumed command of the Stevens, Constable had already developed into a veteran officer. He received his first commission as third lieutenant in 1852, made his way up the ranks and, by 1858, had become executive officer of the new cutter Harriet Lane. Constable had served as executive officer under distinguished cutter captain John Faunce on April 12th, 1862, when Harriet Lane fired the first naval shot of the Civil War near Fort Sumter, South Carolina.

On May 8th, Constable commanded the Stevens when she had another opportunity to engage CSS Virginia. The gunboat accompanied the Monitor and several Union warships to engage Confederate batteries in Hampton Roads and draw Virginia out of her protected anchorage. With President Abraham Lincoln observing from a steam tug, the Union vessels shelled Confederate positions near Norfolk. The Confederate ironclad emerged briefly to threaten Union naval forces but eventually declined the uneven fight and returned to her anchorage. By May 10th, Confederate forces had evacuated Norfolk, leaving the deep-draught Virginia with no defensible homeport or feasible escape route. The Confederates stripped Virginia of her cannons, and, on the evening of the 10th, her commanding officer ordered the ironclad run aground and set her on fire. Early the next morning, flames reached the ironclad’s magazine and blew up what remained of the historic warship.

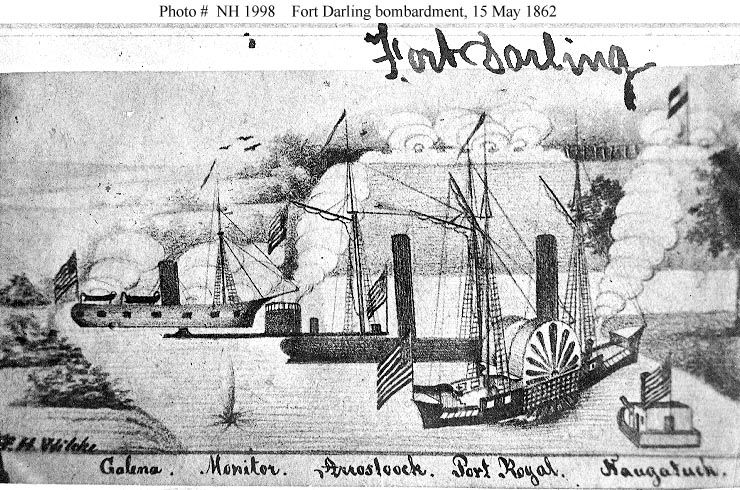

After the destruction of CSS Virginia, Union army general George McClellan requested that the Union Navy send warships up the James River to threaten Richmond from the water. To fulfill this request, the Navy assigned Commodore John Rodgers command of the James River Squadron, including wooden warships Aroostook and Port Royal, ironclads Monitor and Galena, and gunboat E.A. Stevens. It would prove the first true test of the Union Navy’s three new iron warships under battle conditions.

Located eight miles south of Richmond with an elevation of approximately 100 feet above the James River, Drewry’s Bluff is one of the highest promontories on the river’s shores. It overlooks the James at a sharp river bend, providing an ideal location for a fortified position to shell approaching vessels. From the bluff, cannon could employ plunging fire on targets with devastating effect. In early May 1862, the Confederates worked feverishly on the bluff’s fortifications, named Fort Darling, in preparation for an expected attack. They sank several vessels in the river as obstructions to navigation and hauled ordnance up the bluff to the fort. When the James River Squadron appeared in the morning of May 15th, the battery included heavy cannons and Confederate naval personnel from the recently scuttled CSS Virginia.

The Battle of Drewry’s Bluff would prove the first true test of the E.A. Stevens under combat conditions. The Union warships had experienced only minor resistance during their passage up the James River, however, at 7:45 a.m., on the 15th, the battle opened when Rodgers’ flagship Galena approached to within 400 yards of the enemy obstructions. The Confederates opened fire and Galena quickly sustained shell hits. Commodore Rodgers calmly moved Galena into position using her anchor and spring lines, so the vessel could pour a broadside into the Confederate positions. Galena fired round after round into the fort and managed to cause some damage, but Galena got far worse than she gave. The ironclad received approximately 45 hits and nearly half of them penetrated her armor.

After Galena contacted the enemy, the USS Monitor made her own approach. The ironclad closed on the fortifications at about 9:00 a.m. and began shelling the Confederate positions. However, the Monitor had been designed for naval combat rather than shore bombardment, so her cannon could not elevate sufficiently to hit the top of Drewry’s Bluff. After causing slight damage to the Confederate fort and sustaining hits from the enemy guns, Monitor retired downstream.

With the narrow river channel at Drewry’s Bluff, the squadron’s vessels could only file in one at a time. So, when the Monitor withdrew, the Stevens moved up to take her place. She submerged to fire her main battery and the gunboat’s ordnance loading system successfully protected the crew from enemy sharpshooters and musket fire. The gunboat sustained no heavy damage from the enemy’s plunging fire, but her captain, Lieutenant Constable, later reported how enemy musket fire hitting his deckhouse’s armor sounded like hailstones raining down in a storm.

The Stevens continued pouring rounds into enemy positions, however, the gunboat suffered from the same problem as the Monitor. Edwin Stevens had designed the gunboat’s main ordnance to battle enemy warships and not shelling land fortifications. In any case, Stevens’s bombardment came to a halt when her 100-pound Parrott rifle exploded. The explosion blew off the gun’s breech and damaged the cutter’s pilothouse and deck. Despite losing her main gun, the Stevens’s crew fought her 12-pound howitzers with canister and solid shot against the enemy’s land forces.

By 11:00 a.m., the squadron’s flagship Galena had suffered severe damage, exhausted her ammunition and sustained many dead and wounded. After four hours of dueling with the Confederates, Commodore Rodgers ordered his flotilla downriver. One of the Stevens’s crew received a shot in the arm, and another suffered a serious contusion, however, the gunboat had experienced relatively few casualties in the hail of musket fire and enemy shells, and her catastrophic ordnance failure. Lieutenant Constable had sustained a severe head injury from shrapnel flying off the exploding Parrott gun but remained at his station directing the broadside guns and commanding the Stevens throughout the rest of the battle.

The James River Squadron retired to Union-held City Point with the Stevens arriving in the evening and the rest of the squadron arrived in the morning of May 16th. Later that day, Rodgers convened a board composed of squadron officers to examine the remains of the Stevens’s Parrott rifle and determine the cause of its failure. The board concluded that rigorous testing and experimental firing before its installation on board the Stevens had weakened the gun, which had been the first of its kind. Meanwhile, the Stevens received the squadron’s wounded and steamed downriver to medical facilities at Fort Monroe, in Hampton Roads.

The E.A. Stevens had been operating in Virginia waters since early April 1862. Even though her main gun remained shattered, Commodore Rodgers chose to retain her in the James River Squadron. Nevertheless, the Stevens saw no serious action after Drewry’s Bluff. On May 26th, the Treasury Department ordered the gunboat to depart Hampton Roads and steam to the Washington Navy Yard for repairs. On the 29th, President Lincoln honored Lieutenant Constable by promoting him to the rank of captain before an audience of his full cabinet. Soon afterward, the Treasury Department transferred Constable to a new assignment away from the war zone. He served over 20 more years but died suddenly in 1888 from wound-related causes while commanding Revenue Cutter Bibb.

By mid-July 1862, the gunboat had made her way to New York City to become a guard ship for the harbor. Months of this monotonous duty likely caused great boredom among the crew requiring her commanding officer to order them thrown in irons on a regular basis. Occasionally, they received a harsher sentence as in the case of the ship’s steward, who “was placed in irons and triced up twelve hours at the expiration of which time he was placed in solitary confinement in double irons for two days for insolence to comdg. officer.” A year later, the gunboat played a small role in battling the infamous New York City Draft Riots. On July 29th, 1863, Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase ordered the gunboat’s name to revert from E.A. Stevens back to Naugatuck, so the gunboat held the name E.A. Stevens for only three years.

The E.A. Stevens battle tested several unique naval technologies including hidden loading systems, rubber recoil absorbers, multiple screws, high-speed water pumps and ballast tanks. The use of ballast tanks in the gunboat proved the most successful application of that technology up to that time. The twin-screw system had proven very useful for speed, maneuverability and aiming the main gun. Despite the success of her innovations, the Stevens’s exploding gun marred an otherwise successful service record.

After the Civil War, the Treasury Department assigned Naugatuck responsibility for patrolling North Carolina’s inland sounds, and she called the city New Bern her homeport. Naugatuck served this duty from late 1865 until the summer of 1889, with periodic trips to New York, Norfolk and Baltimore for maintenance and repairs. Throughout her career as a gunboat, the E.A. Stevens/Naugatuck never belonged to the U.S. Navy, and she remained a revenue cutter in the long blue line.

-USCG-