This is the true story of U.S. Public Health Service medical officer, Samuel Johnson Call, who served with the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, a forerunner of the U.S. Coast Guard. He completed a 1,500-mile journey in Alaska to help whalers trapped in ice during the harsh winter of 1897-1898. Since the early 1870s, Public Health Service officers have been assigned to the Coast Guard and its forerunners—often aboard cutters. Medical, dental, and nurse officers have served the Coast Guard and other services with many sustaining injuries or losing their lives.

Arctic people hunted whales in the Arctic Ocean for many centuries before the arrival of whaling ships. Businesses from around the world sought baleen, sometimes called “whalebone” (although it is not bone), to make various products. Baleen whales do not have teeth and use it to collect shrimp-like krill, plankton and small fish. Whale oil and baleen were highly valued in Europe and America. Manufacturers used whale oil for cooking and lighting, and baleen for other purposes such as women’s clothing. Because of the difficulty locating whales in the Atlantic, the American whaling fleet sailed to the Arctic.

.jpg?ver=QCpsNCZsmfW17JqhNtxKYA%3d%3d)

Samuel Johnson Call was born in Missouri in 1858 and grew up in California. He received his medical degree from San Francisco’s Cooper Medical College, a predecessor of the Stanford Medical School. In his early twenties, Call worked with the Alaska Commercial Company. He traveled and met revenue cuttermen, including the famed Black officer Captain Michael Healy. Interestingly, Black whalers were some of the earliest Americans to reach Alaska because whaling in the 19th century was one of the most ethnically diverse industries in the country. In 1890, Call left the Alaska Commercial Company and was commissioned into the Public Health Service. In 1891, he was assigned to the sail-and steam-powered Revenue Cutter Bear. Aboard the Bear, Call served with Healy until Captain Francis Tuttle took command in 1896.

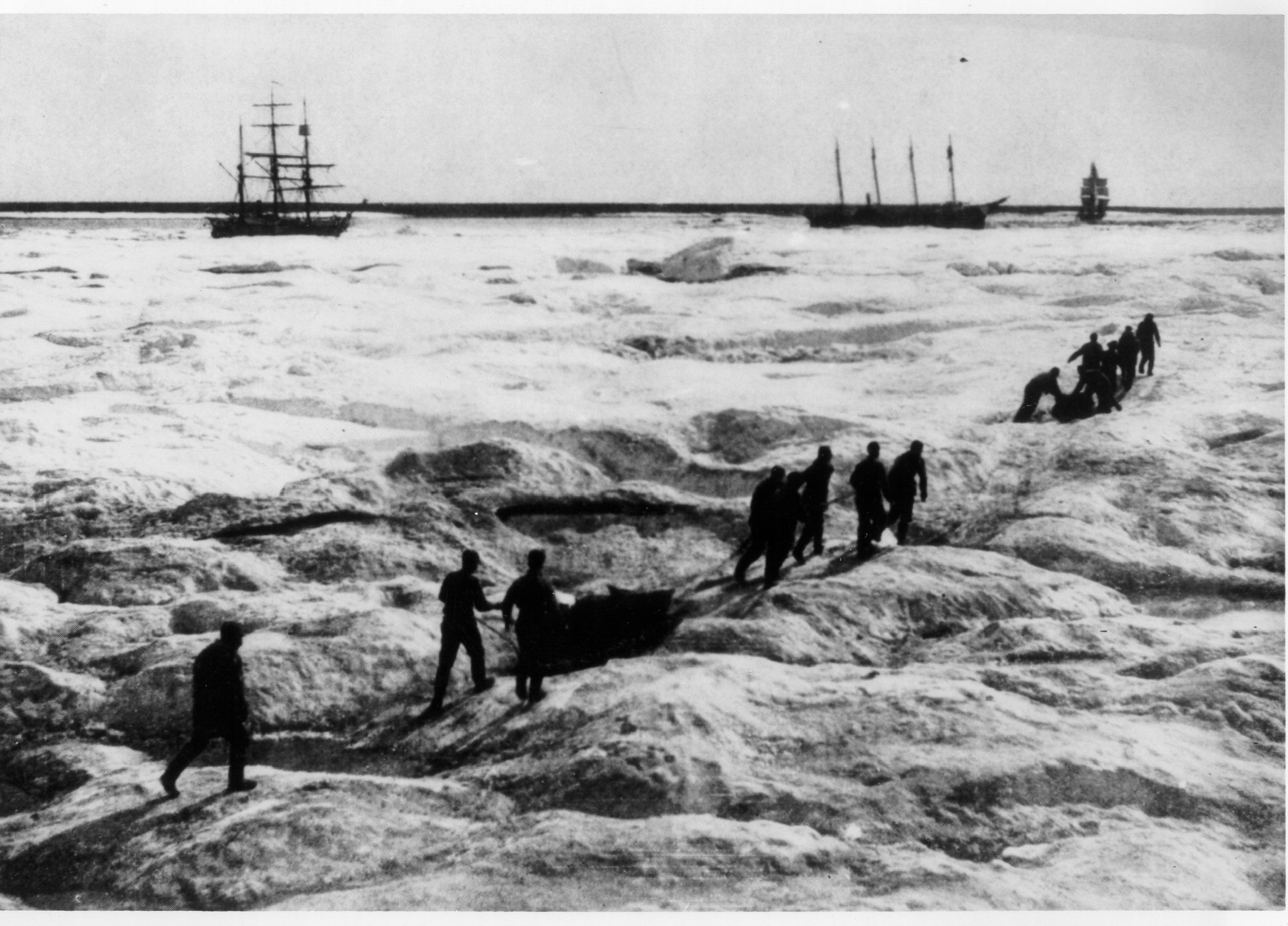

In the fall of 1897, eight whaling vessels became trapped in ice near Point Barrow (now named Nuvuk), Alaska. Unfortunately, nearly 300 men were stranded aboard the ships. The concern was that these men would starve to death. A plan was developed to deliver several hundred reindeer as food delivered by crewmembers from the Bear. President McKinley authorized Captain Tuttle, skipper of the Bear to deploy a rescue team led by his executive officer, 1st Lieutenant David Jarvis along with 2nd Lieutenant Ellsworth Bertholf and Surgeon Call. Deploying on November 27, 1897, the rescue mission became known as the “Overland Relief Expedition.”

.jpg?ver=9upLPVBR4_ZqngSvb-RCGw%3d%3d)

The wooden cutter Bear was unable to push through thick winter ice, so Captain Tuttle put the rescuers ashore at Cape Vancouver, Alaska. This unprecedented rescue began on December 16th, with sleds pulled by dogs and reindeer, and men on snowshoes. Native Alaskan herders and guides Charlie Antisarlook and his wife Mary, who could speak Inupiaq, Russian, and English; and expert herder William Lopp, superintendent of the Teller Whaling Station, proved invaluable to the mission. Located near Point Barrow, Cape Smythe Whaling and Trading Company owner Charles Brower had provided the stranded whalers with food and shelter, so the reported situation of these men was not as dire as initially feared.

Call served as cook and primary photographer for the expedition. His medical services were in constant demand, and he helped everyone, including natives. He treated frostbite, scurvy, snow blindness, influenza, sunburn, and other Arctic medical conditions. The 1,500-mile trek included harrowing experiences in the frigid weather. The team arrived in Point Barrow on March 29, 1898, with almost 400 reindeer. Some of the deer were emaciated at arrival, but their meat was crucial in feeding the starving whalers and halting the spread of scurvy. As a result of the rescue expedition, no whalers were lost to starvation.

President McKinley authorized Jarvis, Bertholf, and Call to receive a specially struck Congressional Gold Medal. Call later resigned his Public Health Service commission in 1899 and set up private practice in Nome, Alaska. The discovery of gold caused the tiny town to swell into a city of 20,000 inhabitants. Call remained in Nome for four years in private practice and served as the community health officer. On one occasion, he embarked on a perilous journey to aid an ailing Catholic priest, Father Aloysius Jacquet, in the remote village of Holy Cross—a 1,200-mile round trip! After departing Nome in 1903, Call returned to the Revenue Cutter Service and served on board the cutters Thetis and McCulloch. Serious health issues forced him to retire in 1908, and he passed away a year later at the age of 50 in Hollister, California.

Today, Call’s namesake unit, the Samuel J. Call Health Services Center at Training Center Cape May, is the largest healthcare facility in the Coast Guard. With a staff of ten Public Health Service medical and dental officers and nearly 100 medical support personnel, the center annually sees over 35,000 appointments and fills over 24,000 prescriptions.

Call’s contributions epitomized the finest in officers of the U.S. Public Health Service and the U.S. Coast Guard, practicing the latter’s core values of “Honor, respect and devotion to duty.”

-USCG-