For centuries, the North Atlantic Sea passage loomed as a navigable challenge to mariners, sea captains, and adventurers alike. For the early sailors who tempted fate pioneering across those icy waters, the environment afforded an opportunity to realize their grit and character. It was a tough job to sail those frigid waters, especially in Antiquity lacking modern comforts. The Viking Lief Erikson first discovered the North Atlantic when he sailed west from Greenland to the east coast of modern Canada. Happenstance led Erickson to discover the New World and, since then, mariners from all walks have retraced the Viking’s early voyages across the legend-shrouded waters of the North Atlantic.

From 1,000 A.D., when Erickson first discovered the transatlantic route, to the 15th century when Columbus landed in the Caribbean, ocean passage across the Atlantic was rare and costly. However, as shipbuilding technology improved, more capable vessels began a semi-regular transit across the North Atlantic. As the frequency of these trips increased, a new foe emerged: icebergs.

Icebergs were observed by those crossing the North Atlantic from Antiquity to the early 1900s. However, the icy monoliths were not taken seriously until 1912. In that year, Royal Mail Ship Titanic set sail on its maiden voyage from Europe to New York City. The Titanic was believed to be “unsinkable” due to hull compartments separated by 16 staunch bulkheads with remote-controlled bulkhead doors. Titanic’s experienced captain, Edward Smith, claimed that “I cannot imagine any condition which would cause a ship to founder. I cannot conceive of any vital disaster happening to this vessel. Modern shipbuilding has gone beyond that.” Despite Captain Smith’s confidence in the vessel’s durability, an iceberg struck the ship a mortal blow in the North Atlantic. Of the 2,240 souls aboard, more than 1,500 individuals perished on the ship’s first and final voyage.

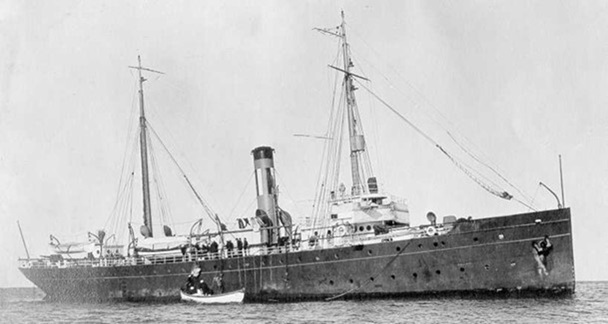

Reacting to the sinking of an “unsinkable ship,” the international community realized that ice posed more of a threat to mariners than previously thought. In 1912, after Titanic’s sinking and loss of life, the U.S. Navy assigned scouting vessels to patrol the Grand Banks off Newfoundland to search for ice and report it to mariners and vessels. In 1913, the Navy could not spare warships for year-round patrols of the northern passages. That year, the Revenue Cutter Service adopted the mission and sent the cutters Miami and Seneca to patrol the Grand Banks. The cutters were charged with searching for icebergs and relaying their coordinates to mariners traversing the transatlantic shipping lanes.

In 1914, the International Ice Patrol (IIP) was officially established by the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) Convention, consisting of 16 nations with shipping interests in the North Atlantic. In 1915, the Revenue Cutter Service and the Life Saving Service merged to form the United States Coast Guard, which continued to perform the IIP mission.

In 1919, the steam-powered Coast Guard cutters Androscoggin and Tallapoosa steamed northward to replace Seneca and Miami. Between 1913, when the first Coast Guard cutter was dispatched to the IIP, and 1990, forty Coast Guard cutters patrolled the northern transatlantic passage searching for icebergs.

Alongside cutter patrols, aviation technology advanced over the years, and flight slowly grew in importance as a method for tracking ice. It was discovered that traversing above the water proved easier and less hazardous to crewmembers navigating the northern regions of the Arctic.

In 1931, the Coast Guard sent LCDR Edward “Iceberg” Smith to accompany the airship Graf Zeppelin on the first aerial polar scientific expedition. As a former ice observation officer in the IIP, LCDR Smith was the perfect fit to survey Arctic ice with aerial photography. LCDR Smith and the Graf Zeppelin flew over the Arctic north of the Russian coast. The zeppelin’s mission proved the concept of aerial exploration of the Arctic. In following years, aerial observation of icebergs became a staple for mapping hazards to mariners traversing the North Atlantic.

In 1946, Coast Guard aircraft stationed at Coast Guard Air Detachment Argentia, Newfoundland, began augmenting the cutter mapping of icebergs and glaciers in the region. Originally, the Coast Guard employed the Consolidated P4Y-1, a four-engine, repurposed B-24 “Liberator” bomber, to scout for icebergs. In 1947, the P4Y-1 was replaced by the Boeing PB-1G reconnaissance aircraft, a repurposed B-17 “Flying Fortress” long-range bomber.

In 1959, the Coast Guard began flying the Douglass R5D-3/4 “Skymaster” for reconnaissance. The Coast Guard also used the R5D to conduct ordnance tests on icebergs, testing high-temperature magnesium and thermite bombs to destroy the hazards. The practice of the ice bombing proved ineffective and was not pursued further.

In 1963, the R5D was replaced with the Coast Guard aerial reconnaissance workhorse that we know and love today, the HC-130 “Hercules.” The first model of the C-130 flown by the service was the HC-130B, which had a Doppler Navigation System. The new aviation platform allowed flight crews to cover larger areas at a faster pace with an increased fuel capacity and more robust engines. In the years following, the capable C-130B model received new radar and navigational systems. To this day, the C-130 model carries out its ice patrol mission; however, in 2010, ice patrols were augmented with the service’s HC-144 “Casa” due to unavailability of the 130’s.

In addition to vessel and aerial ice reconnaissance patrols, the Coast Guard began using satellite technology to pinpoint icebergs. In 1966, the service’s Oceanographic Division extracted data from satellite photographs taken by the N.E.S.C. ESSA satellite and determined the location of ice in the Northwest Passage. The data was transmitted to Coast Guard Ice Patrol units that validated the data collected from the satellite. This early application of satellite reconnaissance proved the potential of satellite technology for iceberg mapping. In the early years of space-based reconnaissance, the data captured by satellites augmented down-range assets but still had to be validated by visual confirmation.

Over the years, the IIP implemented different satellite technologies to augment the ice detection mission. In 2010, it initiated a study using commercial satellites for IIP operations. This study aimed at reducing the dependance on Coast Guard aircraft to visually confirm ice formations. In 2011, satellite imagery was compared to on-scene ice operations and found to have an accuracy rating of nearly 75 percent. In 2016, the IIP officially adopted satellite reconnaissance as a secondary method for detecting ice and now relies on both aerial and satellite data to detect and identify looming bergs. From 2017 on, satellite technology has improved dramatically and is now a vital component of the IIP’s ice detection methodology. By 2022, 90 percent of all ice detected by the IIP was identified via satellite imagery.

Clearly, ice and the search for it have become a vital aspect of the Coast Guard’s mission set. For decades, we have provided mariners and sea captains with data that improves the odds of safe passage through icy waters, and we continue to do so today. Mariners rely on the Coast Guard and its advanced technology to provide critical iceberg data.

As we look into the future and examine the past, the question arises: What will the future of ice detection look like? Undoubtably, it will look very different. Today, as we stand on the edge of technological change, we can only guess about the future of ice detection. Will it come in the form of A.I. guided drones, or perhaps unmanned watercraft? Will Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellites become accurate enough that drones and craft are rendered useless? The answer is unclear. What we do know is that as we move into the future and northern crossings become more commercially and strategically important, the United States must maintain its ability to detect and track icebergs. And who better equipped than the U.S. Coast Guard to embrace this challenge and remain the “tip of the spear” in this mission.

-USCG-