At five o’clock on the morning April 18, 1906, the streets of San Francisco had j ust begun to stir with activity. Twelve minutes after the hour, a severe earthquake, lasting more than a minute, jolted the city. The pavement undulated, buildings shook and crumbled to the ground, and shocks severed gas mains spawning raging fires downtown. The destruction of the city and outlying areas left hundreds of thousands of residents homeless, killed over 450 men, women, and children, and injured thousands more. The 1906 earthquake ranks as the most tragic event in California history and one of the worst natural disasters in U.S. history. The coverage of this event is filled with tales of courage, yet there are certain heroes who never received mention. These were the men of the Revenue Cutter Service who played a vital role during the hours and days following the quake.

ust begun to stir with activity. Twelve minutes after the hour, a severe earthquake, lasting more than a minute, jolted the city. The pavement undulated, buildings shook and crumbled to the ground, and shocks severed gas mains spawning raging fires downtown. The destruction of the city and outlying areas left hundreds of thousands of residents homeless, killed over 450 men, women, and children, and injured thousands more. The 1906 earthquake ranks as the most tragic event in California history and one of the worst natural disasters in U.S. history. The coverage of this event is filled with tales of courage, yet there are certain heroes who never received mention. These were the men of the Revenue Cutter Service who played a vital role during the hours and days following the quake.

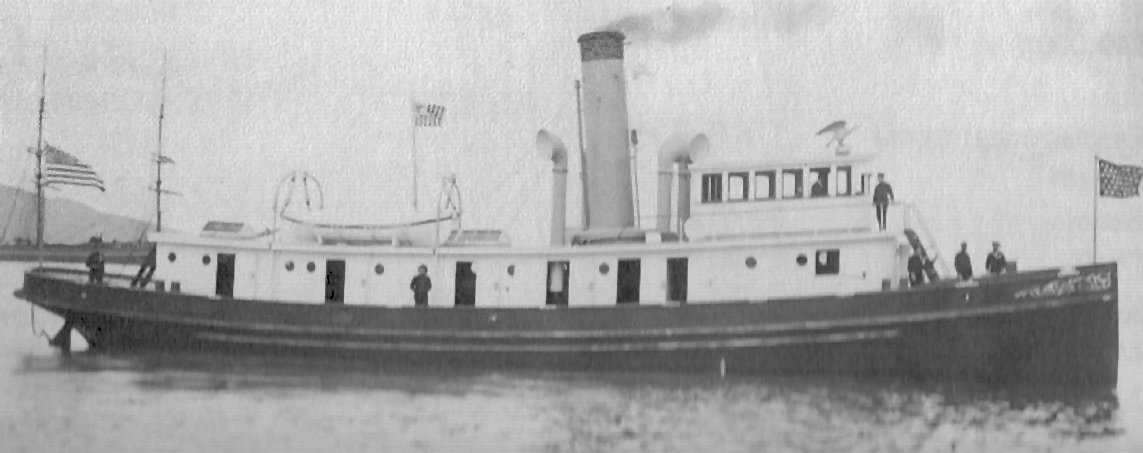

The day of the quake, the cu tter Golden Gate lay in San Francisco Harbor. Shortly after the earthquake, First Lt. Frederick G. Dodge, commanding the Revenue Cutter Golden Gate, got his steamer underway. Proceeding to Boole’s Shipyard in Oakland, he embarked a detachment of men from the cutters Bear and Thetis. Steaming back to San Francisco, he landed these men at Pier #7 at the foot of Pacific Street and sent them to help guard the Appraiser’s Building, temporary home to the U.S. Customs House.

tter Golden Gate lay in San Francisco Harbor. Shortly after the earthquake, First Lt. Frederick G. Dodge, commanding the Revenue Cutter Golden Gate, got his steamer underway. Proceeding to Boole’s Shipyard in Oakland, he embarked a detachment of men from the cutters Bear and Thetis. Steaming back to San Francisco, he landed these men at Pier #7 at the foot of Pacific Street and sent them to help guard the Appraiser’s Building, temporary home to the U.S. Customs House.

Dodge offered the cutter’s services to the local and state authorities, which assigned the Golden Gate to duty at the south side of Pier #10 at the foot of Howard Street. Proceeding to Pier #10, the cutter served there as one of only four government vessels fighting fires along the waterfront. Dodge made the cutter fast to the south side of the pier and ran the cutter’s fire hose out to begin extinguishing flames.

Dodge offered the cutter’s services to the local and state authorities, which assigned the Golden Gate to duty at the south side of Pier #10 at the foot of Howard Street. Proceeding to Pier #10, the cutter served there as one of only four government vessels fighting fires along the waterfront. Dodge made the cutter fast to the south side of the pier and ran the cutter’s fire hose out to begin extinguishing flames.

The Golden Gate remained at Pier #10 until 6:15 that evening when Dodge received an urgent request to steam south to the Pacific Mail Docks in order to save “life and property.” Within minutes, the Golden Gate hastened to the north side of these docks where Dodge found the area in chaos. The fire had moved so fast that about 200 people were walled in on three sides by burning buildings. With escape impossible, everyone on the pier began to panic. By 6:45, the crew ran a hose out and began spraying water on the dock. At first, Dodge believed he had arrived too late but his men carried the hose so close to the fire that the heat blistered their hands and faces. His men fought back the “seething mass of burning houses and lumber” by covering themselves with wet blankets. Dockhands formed a special squad to keep their clothes wet. The cutter was moored so close to the flames that the heat blistered its paint.

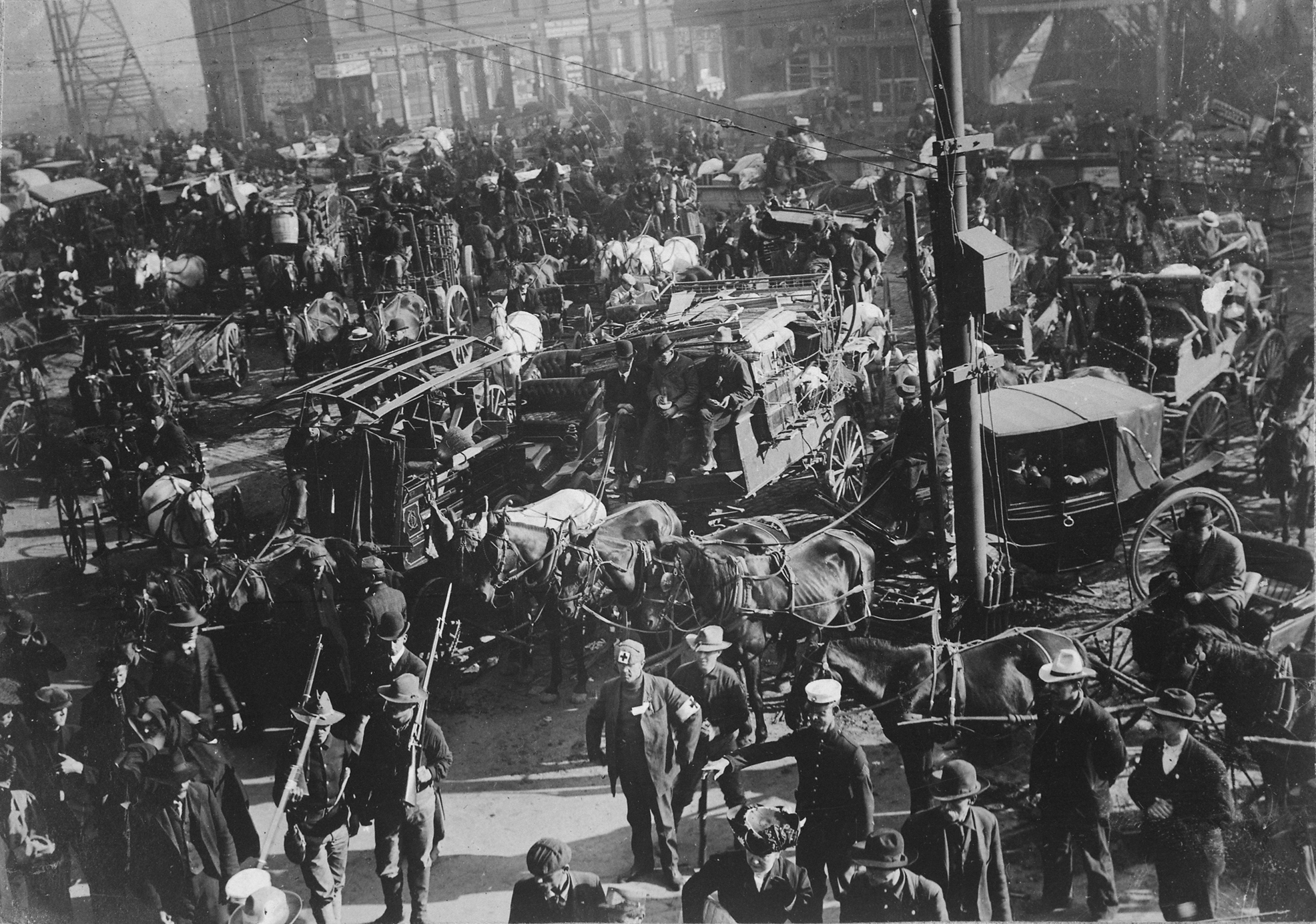

While fighting the blaze, Dodge witnessed human nature at its worst. The crowd near the waterfront had become frenzied and broke into liquor stores, some even lapping up alcohol that ran in the gutters. Many of the refugees were “helplessly drunk” to prepare themselves for death. Because drunks interfered with fire fighting efforts, Dodge had to “use almost extreme measures to subdue them.” Dodge and his men carried aboard the cutter those too drunk to move. About 60 people escaped from the flames in this way. With the flames in check, about 100 of the roving homeless came aboard the cutter for the night.

Immediately after putting out the fire at Pier #10, Dodge sent his men into the offices of the Pacific Mail Company to transfer its papers to the cutter. He then moved the Golden Gate to the south side of the dock to check the flames creeping up that side. From 11:45 p.m., until 12:30 a.m., cuttermen fought the flames on the dock and stood by until 8:00 in the morning of the 19th. Many considered the Pacific Mail Docks the most important waterfront facilities in San Francisco. The state superintendent of wharves valued the Pacific Mail wharves, buildings, and cargoes worth $3,000,000. Had they burned, the fire might have destroyed the remaining line of wharves.

Dodge sent all of his refugees ashore on the morning of the 19th and proceeded with the Golden Gate to Meiggs Wharf and Black Point, on the north side of San Francisco. There, state authorities instructed Dodge to embark refugees and transport them to various points in the Bay. This assignment continued for most of the day. At 2:00 that afternoon, Dodge and his men brought on board a number of trunks and cases containing $23,000,000 of negotiable notes and securities from the Crocker Woolworth National Bank. An armed guard stood watch over these valuables day and night for several days.

On the 20th, as fires still raged out of control in many parts of the city, the Golden Gate transported firemen to Black Point. The cuttermen loaded five tons of coal and then delivered it to Meiggs Wharf to fuel the boilers of the city’s fire engines. The firemen asked Dodge to move the Golden Gate near the foot of Mason Street, so his men could connect the ship’s pump to a disabled fire engine. Complicating this effort were the different sizes of couplings used by federal and municipal governments. Finally finding the proper combination of fittings, Golden Gate’s pumps began pumping water to the fire engine nearly a mile distant. This operation worked well until the fire shifted, driving the flames parallel to the waterfront. Panic erupted and people began crossing over the hose with retreating vehicles that threatened to cut the line. Dodge stationed his men at the street intersections with orders to shoot anyone attempting to drive over the hose. Eventually, the flames became so intense that Dodge recalled his men to the cutter and took aboard refugees that had no way to escape. The Golden Gate remained at the foot of Mason Street to assist any other refugees until flames and scorching heat forced the cutter to retreat.

The Golden Gate steamed to Sausalito, on the north side of the Bay, and deposited the refugees. On the return trip to San Francisco, Dodge spotted the merchant brig Lurline flying a distress signal. The cutter stood alongside and put a boarding party on the brig. Once aboard, the cuttermen found that crewmembers had threatened mutiny. Dodge arrested two mutineers, and transported them to the cruiser USS Marblehead locking them in the brig.

The Golden Gate then headed back to th e San Francisco’s North Beach waterfront and found that the fire had consumed the western part of the district. As the fire swept eastward, Dodge attacked it by moving the cutter to the west side of the Lombard Street Wharf. He ran out a hose and connected it with a city water line at 4:45 p.m. For a number of hours, his crew fought the flames and saved the piers between Lombard Street and the ferries. After these piers were secured, his men spotted smoke billowing from under the eaves of the Sea Wall U.S. Bonded Warehouse. The cuttermen climbed on the roof, cut part of it away and dragged a hose into the opening, saving the building.

e San Francisco’s North Beach waterfront and found that the fire had consumed the western part of the district. As the fire swept eastward, Dodge attacked it by moving the cutter to the west side of the Lombard Street Wharf. He ran out a hose and connected it with a city water line at 4:45 p.m. For a number of hours, his crew fought the flames and saved the piers between Lombard Street and the ferries. After these piers were secured, his men spotted smoke billowing from under the eaves of the Sea Wall U.S. Bonded Warehouse. The cuttermen climbed on the roof, cut part of it away and dragged a hose into the opening, saving the building.

The next day, the Golden Gate ferried refugees to various points on the Bay’s shoreline. The crew also worked to distribute food to the destitute and return the records of the Pacific Mail Company. On the 22nd, the crew landed the securities and valuables of the Crocker Woolworth National Bank at Pier #9 at Broadway Street. The cutter then came under the control of the Navy until May 1st. Under naval orders, Dodge and his men continued distributing food and performing nightly patrols along the waterfront, and preparing hundreds of hot meals for the destitute.

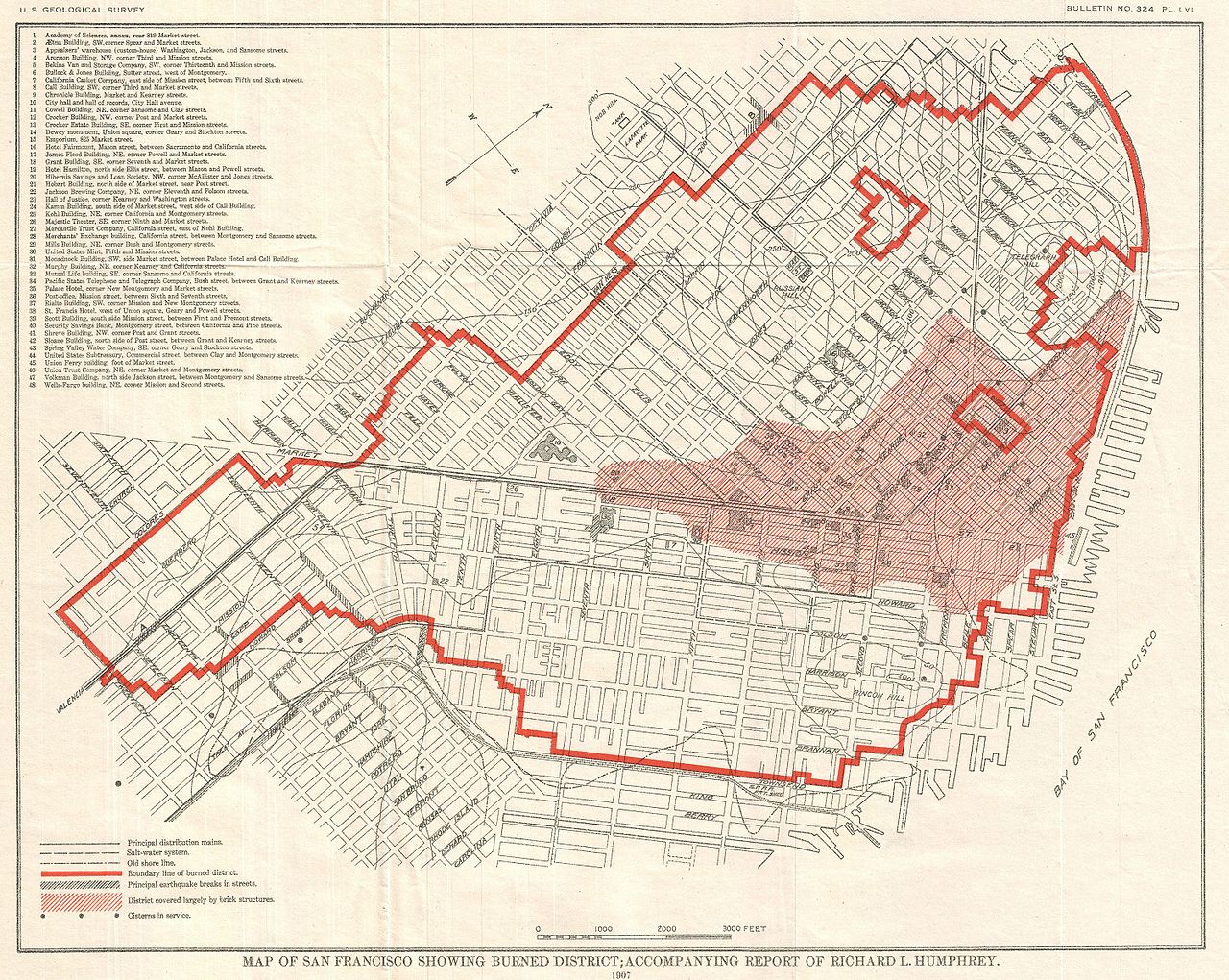

The San Francisco Earthquake had displaced about 250,000 people and the devastation covered nearly 500 city blocks. After the fires had burned out, all of the officers and men of the Revenue Cutter Service aided the U.S. Army in the relief effort and helped to establish and maintain law and order throughout the San Francisco Bay Area. For at least a month, the cuttermen distributed food, meal tickets, and passes. They settled disputes, made sanitary inspections of refugee camps, assisted people looking for frie nds and relatives, and helped maintain 150 relief stations, brought food and fresh water into the city, and patrolled the docks. The Revenue Cutter Service received special thanks from President Theodore Roosevelt for its “prompt, gallant, and effective work.”

nds and relatives, and helped maintain 150 relief stations, brought food and fresh water into the city, and patrolled the docks. The Revenue Cutter Service received special thanks from President Theodore Roosevelt for its “prompt, gallant, and effective work.”

In this crisis, the cutter Golden Gate and its valiant crew lived up to the Coast Guard motto—Semper Paratus—“Always Ready.” Lt. Dodge paid an extreme compliment to the men under his command writing that they showed great courage and had “worked day and night without complain of hunger or weariness, and obeyed orders. . . with cheerfulness and alacrity.”