The Long Blue Line blog series has been publishing Coast Guard history essays for over 15 years. To access hundreds of these service stories, visit the Coast Guard Historian’s Office’s Long Blue Line online archives, located here: THE LONG BLUE LINE (uscg.mil)

Asian nationals began serving in the United States Coast Guard 175 years ago, playing an important role in the history of the Coast Guard’s ancestor agency of the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service. Enlisting foreign nationals in the Pacific began in 1849, when 17 Hawaiian seaman signed-on to serve aboard Revenue Cutter C.W. Lawrence, the first cutter to sail the Pacific.

Cutter muster rolls tell the story of native Asian participation in the service with Asian names appearing on muster rolls after the Civil War. For example, 1866 saw enlistment of Asian nationals aboard Revenue Cutter Lincoln, based in Port Townsend, Washington Territory. These men included Wardroom Steward Zuing Chung, Cabin Steward Ah Ling, Ship’s Cook Sam Chung, and Officer’s Cook Qim Joy.

The purchase of Alaska in 1867 expanded revenue cutter operations in the Pacific presenting more opportunities for Chinese and Japanese nationals to enlist aboard revenue cutters. For example, in 1878, muster rolls show ten Chinese nationals and three Japanese nationals serving aboard San Francisco-based revenue cutter Corwin. These men filled various food service and domestic positions in ratings such as Steward and “Boy.” During the late 1800s, virtually every West Coast-based cutter employed Asian servicemembers of this kind.

After the 1898 Spanish-American War, the U.S. annexed the former Spanish colony of the Philippines. Two years later, President William McKinley signed an executive order allowing the American sea services, such as the U.S. Navy and Revenue Cutter Service, to recruit native Filipinos to serve in domestic and food service positions. As a result, hundreds of Filipinos volunteered to serve in the ratings of Steward, Cook and Boy for the Revenue Cutter Service and, after 1915, in the modern Coast Guard.

During the early 20th century, the number of Asian servicemembers continued to grow. For example, the 1917 muster roll of San Francisco-based cutter McCulloch showed over half the positions of Boy were filled by Philippine nationals. McCulloch’s food service positions of Cook and Steward were filled by Japanese nationals, including Cook Yone Kamiyama, Wardroom Steward K. Matsumori, and Cabin Steward Yosamatsu Minatoya. Minatoya was born in Ishikawa, Japan, and began serving in the Revenue Cutter Service in 1903 as a Steward aboard revenue cutters such as the Thetis. He was serving on the McCulloch in 1917, when the cutter suffered a collision and sank off the California coast. Minatoya survived the sinking and remained with the Coast Guard until 1930 after over 25 years of service.

During the early 20th century, the number of Asian servicemembers continued to grow. For example, the 1917 muster roll of San Francisco-based cutter McCulloch showed over half the positions of Boy were filled by Philippine nationals. McCulloch’s food service positions of Cook and Steward were filled by Japanese nationals, including Cook Yone Kamiyama, Wardroom Steward K. Matsumori, and Cabin Steward Yosamatsu Minatoya. Minatoya was born in Ishikawa, Japan, and began serving in the Revenue Cutter Service in 1903 as a Steward aboard revenue cutters such as the Thetis. He was serving on the McCulloch in 1917, when the cutter suffered a collision and sank off the California coast. Minatoya survived the sinking and remained with the Coast Guard until 1930 after over 25 years of service.

In the Interwar Period, Filipino servicemembers dominated the domestic service ratings. A 1937 U.S. Public Health Service report showed 364 non-naturalized Filipinos serving out of a total 757 men in the Steward Section of the Cutter Forces Branch. During this period, Unalga’s Filipino Officers’ Steward Third Class Ramon Jasalim suffered mortal injuries, becoming the first known Asian servicemember to die in the line of duty. Meanwhile, Philippine native Modesto Magbanoa served in the Coast Guard in World War I and World War II, before retiring as a Steward’s Mate First Class.

Japanese servicemembers suffered greater hardships than members of other Asian groups. Born in 1867, in Yokohama, Japan, Matsunosuki Ono began serving in 1905 as a Commissary Steward aboard cutters and then at the Coast Guard Academy until he died in 1937 at the age of 69. He was the first known Asian servicemember to advance to Chief Commissary Steward, giving him Chief’s pay, but no rank or authority beyond the Steward’s rating. He applied for U.S. citizenship, but finally received it two months after he died. Japanese native Sehsh Heado enlisted in Port Townsend, Washington, and served as an Officers’ Steward until his death in 1928. The Coast Guard base at Port Townsend paid for his funeral expenses and interment.

When the Philippines fell to the Japanese in the spring of 1942, President Manuel Quezano’s exiled government moved to the United States. In a ceremony attended by President Franklin Roosevelt, Quezon formally handed over the 68-foot former yacht Bataan and its Filipino crew to the U.S. Coast Guard, stating:

When the Philippines fell to the Japanese in the spring of 1942, President Manuel Quezano’s exiled government moved to the United States. In a ceremony attended by President Franklin Roosevelt, Quezon formally handed over the 68-foot former yacht Bataan and its Filipino crew to the U.S. Coast Guard, stating:

“The Filipino officers and crew who will man this vessel are now regular members of the Coast Guard Reserve. They, and this Coast Guard patrol boat, represent the desire of every one of the 17 million Filipinos, whether under enemy domination or on free soil, to go into action again in the fight for freedom.”

The Bataan was officially accepted for duty by Coast Guard Commandant Russell Waesche and designated CG-68009. After fitting out with guns and depth charge racks, the cutter sailed south to the Seventh District and San Juan, Puerto Rico, to serve as an offshore patrol boat and subchaser.

CG-68009 was likely assigned to Puerto Rico for two reasons. First, Coast Guard patrol vessels and subchasers were in high demand in the Caribbean for inter-island convoy escorts and warding off U-boats cruising those waters. The second reason was language. All of CG-68009’s crew were not only experienced mariners, but they were also fluent in several languages. Indeed, each of the crew spoke English as well as one or two Philippine dialects. More importantly, they were fluent Spanish speakers. Given the Coast Guard’s responsibility to protect Caribbean shipping, where many local mariners spoke no English, fluency in Spanish was critical.

CG-68009 was likely assigned to Puerto Rico for two reasons. First, Coast Guard patrol vessels and subchasers were in high demand in the Caribbean for inter-island convoy escorts and warding off U-boats cruising those waters. The second reason was language. All of CG-68009’s crew were not only experienced mariners, but they were also fluent in several languages. Indeed, each of the crew spoke English as well as one or two Philippine dialects. More importantly, they were fluent Spanish speakers. Given the Coast Guard’s responsibility to protect Caribbean shipping, where many local mariners spoke no English, fluency in Spanish was critical.

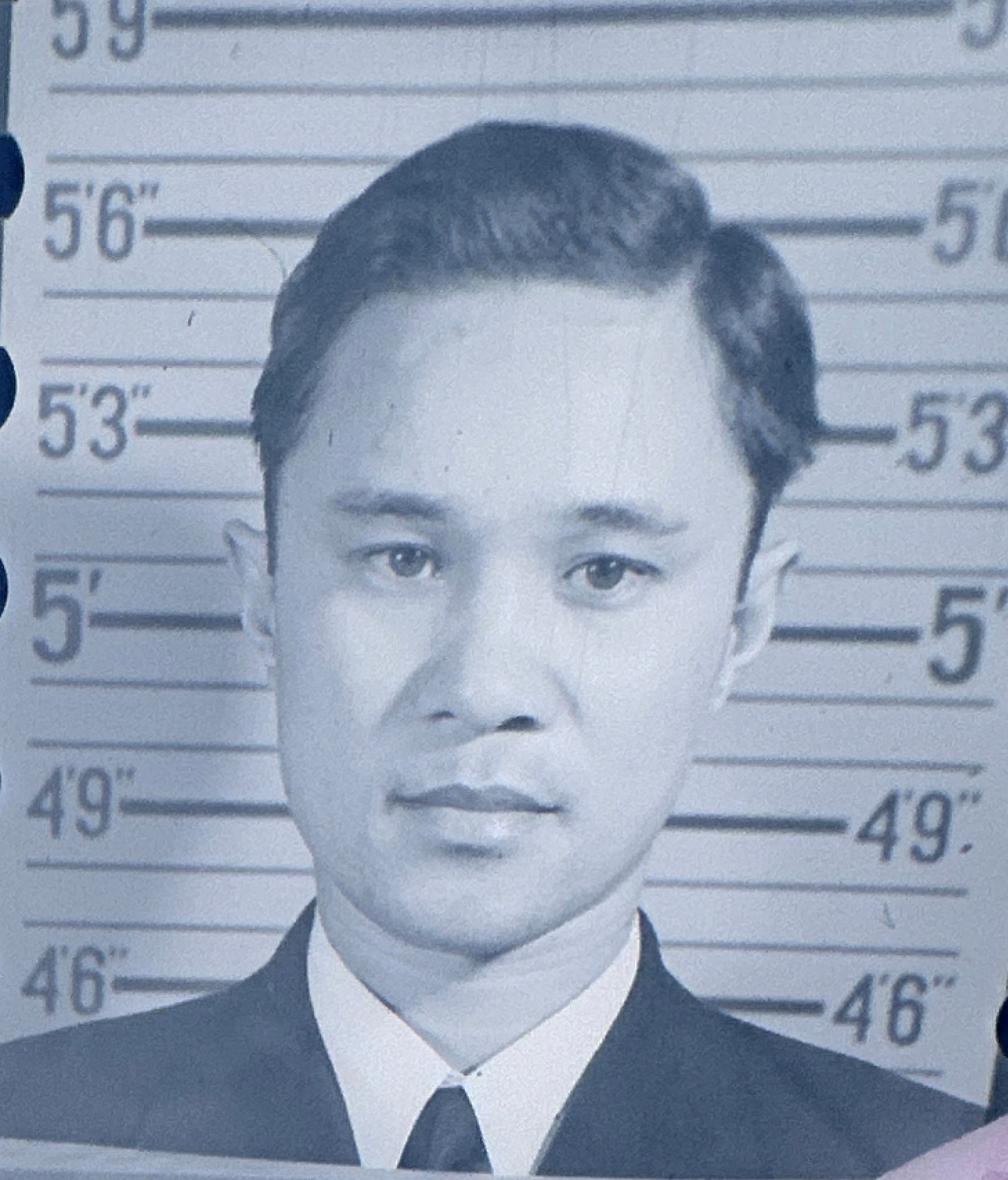

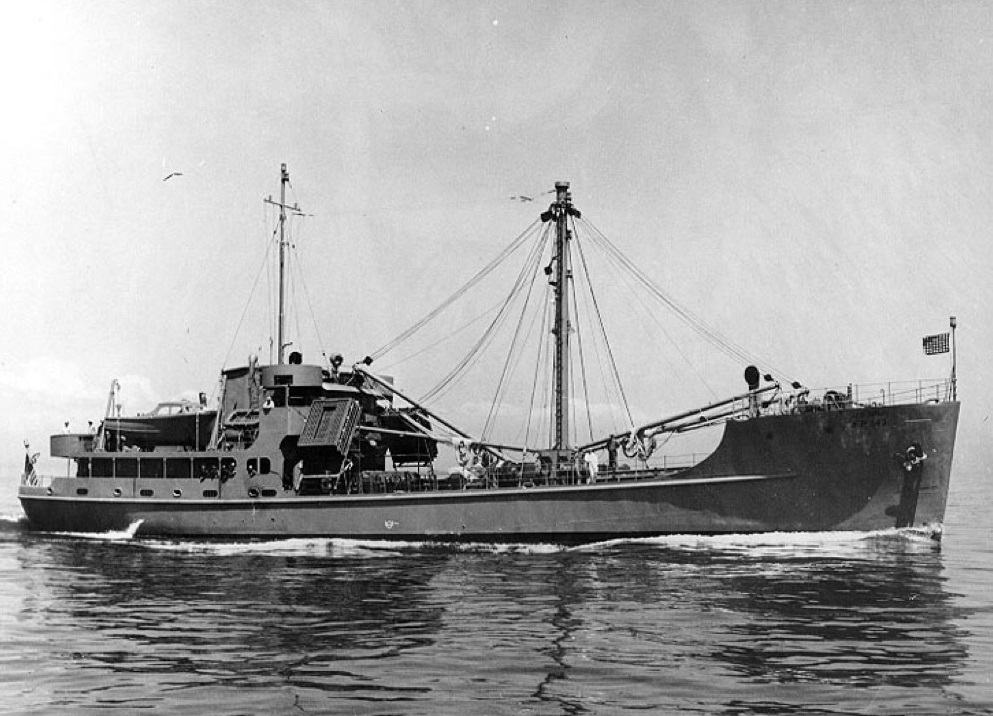

After serving two years aboard CG-68009, the officers and crew shipped out to the Pacific. They would be assigned to other Coast Guard-manned vessels including the Navy cargo vessel, USS Albireo (AK-90). CG-68009’s enlisted crew and executive officer, Lieutenant junior grade Conrado Aguado, were assigned to the Albireo. Under the command of another native Filipino Coast Guard officer, Commander Carmelo Manzano, this cargo vessel steamed across the Pacific to supply various island bases. CG-68009 commander, Lt. Juan “John” Lacson, became the commanding officer of the Coast Guard-manned Army vessel FS-171, a 177-foot coastal and inter-island cargo vessel designed for small harbors and confined waters such as those found in the Philippine islands.

After serving two years aboard CG-68009, the officers and crew shipped out to the Pacific. They would be assigned to other Coast Guard-manned vessels including the Navy cargo vessel, USS Albireo (AK-90). CG-68009’s enlisted crew and executive officer, Lieutenant junior grade Conrado Aguado, were assigned to the Albireo. Under the command of another native Filipino Coast Guard officer, Commander Carmelo Manzano, this cargo vessel steamed across the Pacific to supply various island bases. CG-68009 commander, Lt. Juan “John” Lacson, became the commanding officer of the Coast Guard-manned Army vessel FS-171, a 177-foot coastal and inter-island cargo vessel designed for small harbors and confined waters such as those found in the Philippine islands.

Asian nationals chose different paths after serving in the Coast Guard. Some sought U.S. citizenship and a new life in America. Others returned to their homeland after serving in the Coast Guard, including the crew of CG-68009. Others chose a third path of acquiring U.S. citizenship and returning to their homeland. For example, former commander of CG-68009, Juan Lacson became a U.S. citizen and served in the Coast Guard Reserve for several years after the war, retiring as a lieutenant commander. During his postwar career in the Philippines, he established the John B. Lacson Foundation Maritime University which is now an accredited academic institution offering undergraduate and graduate education.

In 1946, the U.S. granted the Philippines complete independence and discontinued the practice of recruiting native Filipinos for domestic service work in the U.S. sea services. However, in 1947, the U.S. and Republic of the Philippines signed an agreement allowing the U.S. to once again recruit citizens of the Philippines for voluntary enlistment in the U.S. military. Enlisting Philippine nationals for domestic service aboard Coast Guard cutters continued for another 20 years, however, after gaining citizenship these men were allowed to change enlisted ratings to non-food service positions or pursue an officer’s commission. Finally, in 1971, this practice was discontinued and all enlisted ratings were opened to Filipino-Americans that qualified by means of education, prior experience and security qualifications.

In 1946, the U.S. granted the Philippines complete independence and discontinued the practice of recruiting native Filipinos for domestic service work in the U.S. sea services. However, in 1947, the U.S. and Republic of the Philippines signed an agreement allowing the U.S. to once again recruit citizens of the Philippines for voluntary enlistment in the U.S. military. Enlisting Philippine nationals for domestic service aboard Coast Guard cutters continued for another 20 years, however, after gaining citizenship these men were allowed to change enlisted ratings to non-food service positions or pursue an officer’s commission. Finally, in 1971, this practice was discontinued and all enlisted ratings were opened to Filipino-Americans that qualified by means of education, prior experience and security qualifications.

The unique system of enlisting foreign nationals, primarily Asian men, to serve in Coast Guard domestic and food service positions remained in place for 130 years. In spite of their national origins and unequal treatment in the service, these men served honorably, with the same loyalty and devotion to duty as their American shipmates.

-USCG-