Kate knew the walk was dark, the work was difficult, and the weather was treacherous. She knew the lighthouse staircase was torturous. She knew the wee hours were tedious. Each dangerous duty was everything that little girls in the 1800s were not supposed to do. After all, women were told they were absolutely, positively not capable of such bravery, courage, or strength. Little girls were supposed to be ladylike, not lighthouse keepers.

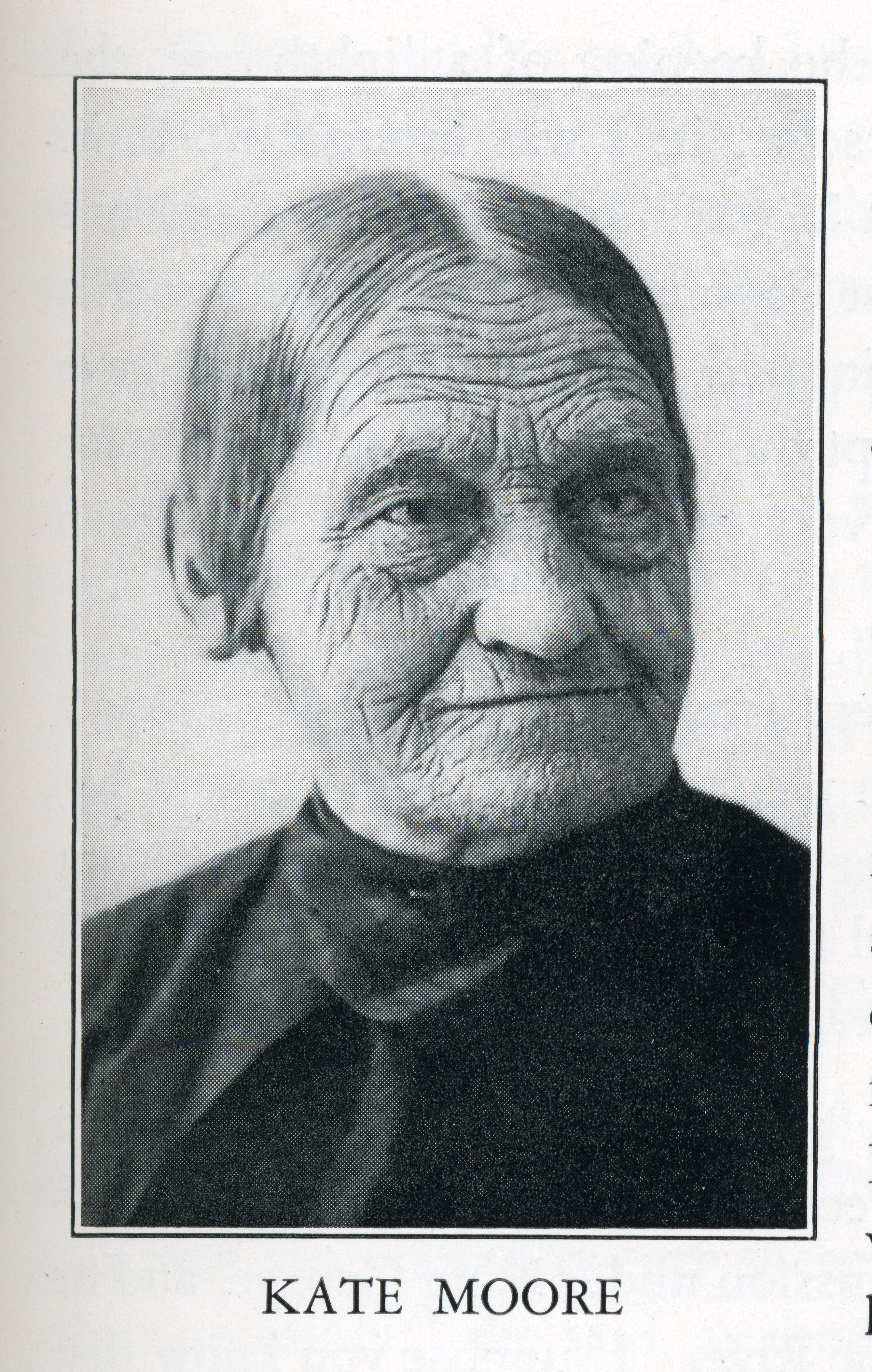

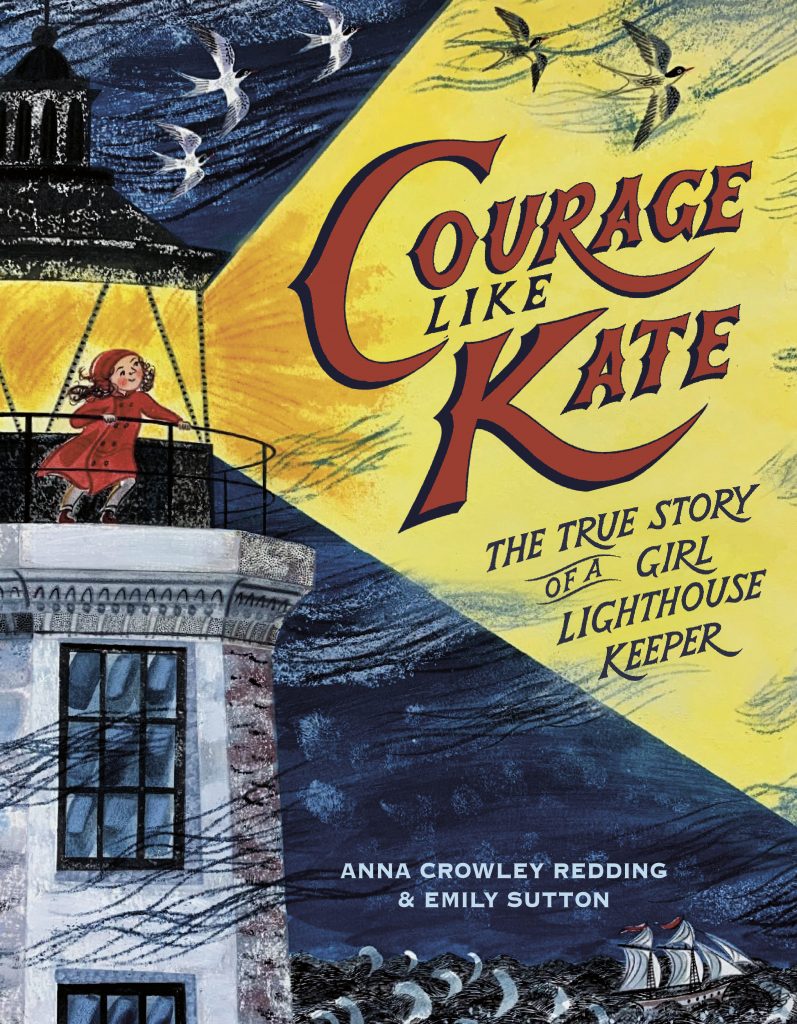

This excerpt from the children’s book Courage Like Kate, The True Story of a Girl Lighthouse Keeper by Anna Redding captures both the physical obstacles and social norms that 12-year-old Kathleen “Kate” Moore overcame to protect those in peril from the sea. The annals of Coast Guard history, and those of its predecessor services, are filled with extraordinary stories of stalwart devotion to duty. Few of those tales are more inspiring than that of the life of Kate Moore, Keeper at Light Station Fayerweather Island. She dedicated most of her life to keeping the light burning and protecting those at sea. Kate Moore was a trailblazer at a time in our history when opportunities for women were very limited. She grew up tending the lighthouse and served the nation for over five decades. Kate Moore’s life is the very definition of devotion to duty.

Fayerweather Island shelters the entrance to Black Rock Harbor on the western shore of Long Island Sound near Bridgeport, Connecticut. In the 18th century, Black Rock was a rapidly developing seaport. The need for a lighthouse on the island to guide ships into the harbor was essential. The first light structure, a 40-foot-tall octagonal wooden tower, and a keeper’s dwelling were constructed in 1808. The Fayerweather Island Light Station, also known as Black Rock Light, was a critical beacon on the busy seaway of Long Island Sound.

Kate’s father, Stephen Moore, a sea captain, was injured while helping a friend with a load of hay. His injuries left him unable to handle some of the physical rigors of shipboard life, so he applied for a position as a lighthouse keeper. Moore was offered, and accepted, the post at Fayerweather Island in 1817. He and his wife Amelia, along with their children, Kathleen (age 4), Mary (age 3), and Alexander (age 2) moved to the island. The new job provided a keeper’s house, a shed, a dock, and land to cultivate. Despite the many challenges, the family adjusted well to its new life on the light station. A hurricane ripped through the island on September 3, 1821, destroying the original wooden light tower. Kate and her family weathered the storm, and a new forty-one-foot-tall light tower constructed of sandstone was completed in 1823. That tower still stands today.

The life-saving beam on Fayerweather Island was first cast by a whale oil spider lamp. The lighthouse apparatus was upgraded to a system with eight lamps and parabolic reflectors in 1830, and in 1854, a fifth-order Fresnel lens was installed. Obviously, the most essential duty of a lighthouse keeper is to tend the lamps that produce the beacon. For most of the Moore’s time at Fayerweather this required climbing the lighthouse’s narrow steps carrying sufficient oil to keep the eight, often temperamental, Winslow Lewis reflector lamps fueled and functioning properly. Tending the beacon could be treacherous, especially for Stephen.

Kate began assisting her father with tasks around the station as a small child. By age 12, she had assumed all the duties Stephen could not accomplish due to his physical limitations, including tending the beacon. Her father and other family members assisted with many tasks, but Kate was, for all practical purposes, the lighthouse keeper. However, her status remained unofficial for decades. As was the common practice of the time, her father retained the official “Keeper” title until he died 1871 at the age of 98. Upon her father’s death, Kate, now 59, was finally appointed Keeper at Light Station Fayerweather Island.

Lightkeeper Kate

Kate’s longevity, the novelty of a female lighthouse keeper, and her many life-saving exploits garnered local notoriety. Over the years, she was interviewed by several newspapers. An article in the New York World published after Kate retired provides interesting, first-hand insights into her life at Fayerweather Island. When asked about the challenges of tending the light as a child, she recalled:

It was a miserable one to keep going, too — nothing like those in use nowadays. It consisted of eight oil lamps which took four gallons of oil each night, and if they were not replenished at stated intervals all through the night, they went out. During windy nights it was impossible to keep them burning at all, and I had to stay there all night, but on other nights I slept at home, dressed in a suit of boys’ clothes, my lighted lantern hanging at my headboard and my face turned so that I could see shining on the wall from the light tower and know if anything happened to it. Our house was forty rods (about 700 feet) from the lighthouse, and to reach it I had to walk across two planks under which on stormy nights were four feet of water, and it was not too easy to stay on those slippery, wet boards with the wind whirling and the spray blinding me.

When asked if she was lonely at the end of career when she lived alone on the island, she added: “I had a lot of poultry and two cows to care for, and each year raised twenty sheep, doing the shearing myself, and the killing when necessary.” In addition to this, she said she read, kept a garden, tended oyster beds, and carved duck decoys for sportsmen and visitors. In an 1878 interview, a New York Sun reporter described Moore, then 66, as a genteel woman whose walls were lined with book-filled shelves and whose house featured wooden duck decoys she’d carved herself. A painting by Dutch painter Reubens that Kate inherited from her mother’s family hung on her wall.

Lifesaver Kate

During the New York World interview, Kate also discussed the dangers of Black Rock Harbor: “Sometimes there were more than two hundred sailing vessels at night, and some nights there were as many as three or four wrecks.” Kate added that one dark night she heard cries of distress coming from the harbor. She went out in the boat with her brother Alexander and their cousin. After an hour’s search they found two men clinging to a capsized boat. The two men stayed at the house with the Moore family, but one died early the next morning. This was just one of the many horrific incidents that Kate experienced. A skilled boat handler, she was credited with saving at least 21 lives. When asked by a reporter about the number of lives she saved, Kate responded, “I wish it had been double that number.”

A Quiet End to a Life of Dedicated Service

Kate retired in December 1878 and bought a house on Main Street (now Brewster Street) in Black Rock near the harbor. She is listed in the 1898 Bridgeport City Directory as “Miss Kate Moore.” At the time of the New York World interview, the reporter indicated that “Kathleen owned her home and had a bank account of $75,000, which she had accumulated during her isolated life on Fayerweather Island.” Kate crossed the bar in 1899 and was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in Mountain Grove Cemetery in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Recognition

In 2014, the Coast Guard named the ninth of its new 154-foot Sentinel-Class cutters in Kate’s honor. USCGC Kathleen Moore (WPC 1109) was commissioned March 29, 2014. The cutter is homeported in Key West, Florida. Kate was further honored on May 8, 2014, when the Coast Guard and Bollinger Shipyards, builder of cutter Kathleen Moore, placed a headstone on her previously unmarked grave. A large stone monument and bronze memorial plaque honoring Kate was erected on the waterfront by the History Committee of the Black Rock Community Council on September 19, 2015.

Courage Like Kate

It is rare for a children’s book to become a primary source for research into the life of a historic figure in Coast Guard history. Courage Like Kate, The True Story of a Girl Lighthouse Keeper is one of those books. Authored by Anna Redding, it does a wonderful job of telling the story of lighthouse keeper Kate Moore. Emily Sutton’s illustrations of Kate trimming the wicks and fueling the cantankerous Winslow Lewis reflector lamps historically accurate. The fact that Kate Moore’s life is the inspiration for a children’s book is a testimonial to her incredible story.

Crowley Redding’s book, along with the grave marker, stone memorial on the waterfront, and a Coast Guard cutter named in her honor are appropriate tributes to the stalwart dedication and extraordinary courage of Kate Moore. She deserves to be remembered.

-USCG-